27 February – 3 March 2026

HIGHLIGHT OF THE WEEK

When AI ethics collide with national security: The Anthropic-Pentagon standoff

In a high-stakes showdown that is redrawing the battle lines between Silicon Valley and the US military, AI firm Anthropic found itself exiled from the Pentagon after refusing to waive its ethical safeguards.

How it started: A contractual dispute. The Pentagon sought assurances that Anthropic’s model, Claude, could be used for ‘all lawful purposes.’ Anthropic pushed back, arguing that such wording did not sufficiently restrict uses the company considers high-risk, particularly mass domestic surveillance and fully autonomous weapons systems. The company requested clearer guardrails.

How it escalated: A supply chain risk designation. Officials signalled that Anthropic risked losing federal contracts and could even face designation as a supply chain risk. The administration ultimately moved ahead with that step, ordering agencies to halt use of Anthropic’s systems and providing a limited six-month wind-down period for existing arrangements.

Supply-chain risk designations are typically for foreign-adversary threats, not for domestic firms negotiating contract terms. Experts and Anthropic argue that such a designation has no clear precedent, and Anthropic plans to challenge it in court.

Enter: The rival company. Into this vacuum stepped OpenAI. Shortly after Anthropic’s blacklisting, OpenAI reached its own arrangement with the Pentagon. The company publicly emphasised that it maintains safety ‘red lines,’ including restrictions related to mass surveillance and the requirement for human oversight in the use of force. CEO Sam Altman indicated that OpenAI shares many of the same ethical concerns Anthropic had raised.

However, Altman ultimately called OpenAI’s contract with the Pentagon rushed, and added on 3 March that the deal would be amended to ensure that the AI system wouldn’t be used for mass domestic surveillance.

The reactions. The episode reverberated throughout the tech world. Major industry groups, including representatives from Amazon, Nvidia, Apple, and others, warned the government against broad use of supply-chain risk designations for US tech companies, fearing chilling effects on innovation and public-private cooperation.

Investors in Anthropic also pushed for de-escalation, worried that the standoff could harm the company’s enterprise business and IPO prospects if key contracts were lost.

However, the day after the Anthropic lost its Pentagon contract, Claude hit number 1 in US app downloads, while US app uninstalls of ChatGPT’s mobile app jumped 295% day-over-day. This suggests that Claude may not lose popularity with users. Additionally, the supply chain risk designation may mean that businesses can work with Anthropic on non-defence-related projects.

Why does it matter? Ultimately, the dispute exposed a deeper structural tension. Advanced AI systems are increasingly central to military planning, logistics, intelligence analysis, and battlefield decision-making. At the same time, leading AI firms have articulated ethical boundaries around surveillance, lethal autonomy, and dual-use risks.

The confrontation between Anthropic and the Pentagon crystallised the question of who determines those boundaries when national security and corporate governance collide.

IN OTHER NEWS LAST WEEK

This week in AI governance

The UN. At the Independent International Scientific Panel on Artificial Intelligence (AI), UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres told experts that they have a huge responsibility to help shape how the technology is used ‘for the benefit of humanity’. As AI development accelerates, the Secretary-General also warned the panel that it is ‘in a race against time.’ Guterres also pointed to earlier work through the UN High-Level Advisory Body on AI, noting that the new scientific panel does not ‘start from zero’. Concluding his remarks, Guterres told the experts: ‘I can think of no more important assignment for our world today.’

UNESCO has signed a cooperation agreement with the National Centre for Artificial Intelligence (CENIA) to promote ethical AI development and strengthen AI education across Chile and Latin America. The partnership will focus on building digital skills, improving AI literacy, and supporting people-centred AI governance through training programmes, educational resources, and multistakeholder collaboration.

The USA. Seven tech giants ( Google, Meta, Microsoft, Oracle, OpenAI, Amazon, and xAI) have signed the White House’s ratepayer protection pledge, encouraging major technology companies to cover the additional electricity costs associated with their AI infrastructure. Participating companies have agreed to finance new power generation resources, upgrade electricity delivery infrastructure and negotiate separate electricity rate structures with utilities and state authorities. The arrangement is designed to ensure that additional energy demand from large data centres does not translate into higher prices for residential consumers.

South Korea and Singapore. South Korea and Singapore have launched a Korea-Singapore AI Alliance, a bilateral initiative to deepen cooperation in AI and related technologies. Announced at the Korea-Singapore AI Connect Summit in Singapore, the alliance aims to create an open innovation ecosystem that connects capital, talent and technology between the two nations, with the goal of enhancing competitiveness in the global AI market and supporting joint development of AI solutions that address regional and global challenges. The partnership includes a pledge to establish a US$300 million global AI investment fund in Singapore by 2030 to support startups and collaborative research.

Child safety online

Yet another country has decided to restrict minors’ access to social media—Indonesia’s Communication and Digital Affairs Minister signed a government regulation that means children under 16 can no longer have accounts on high-risk digital platforms. This will reportedly include YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, Threads, X, Bigo Live and Roblox. Implementation of the regulation will begin gradually from 28 March.

The UK is still debating. The country has launched a public consultation examining whether children under 16 should face restrictions or a potential ban on social media use. Young people, parents and educators are being invited to share views before ministers decide on future policy. Potential measures could include setting a minimum age limit for social media, restricting harmful features such as infinite scrolling, and examining protections against children sending or receiving explicit images. The consultation will also explore restrictions on children’s use of AI chatbots and limits on VPN use where it undermines safety protections. The government intends to act swiftly on its findings within months by introducing targeted legal powers that can be enacted rapidly as technology evolves.

Meanwhile, China’s draft measures that classify and regulate online information that may harm minors’ physical and mental health went into effect on 1 March. Covered content includes material inducing unsafe behaviour, extreme emotions, discrimination, unhealthy lifestyles, irrational consumption, celebrity worship, or distorted values such as hedonism and pseudoscience. The rules also restrict the misuse of minors’ images and personal data. Providers of algorithmic recommendation systems and generative AI services are required to strengthen and refine their security governance frameworks and technical safeguards, and are prohibited from promoting or distributing online content that could negatively impact minors’ physical or psychological well-being.

A procedural setback in the European Parliament has cast uncertainty over plans to extend temporary EU rules allowing tech companies to voluntarily scan their services for child sexual abuse material (CSAM). The temporary regime, introduced as a stopgap while the EU negotiates the Child Sexual Abuse Regulation, is due to expire in April 2026. The European Commission has proposed extending it by two years, though some MEPs had pushed to limit the extension to one year. On Monday, Parliament’s civil liberties committee voted on amendments to a draft report on extending the current derogation from EU privacy rules, but ultimately failed to adopt the final text, sending the file to a plenary vote in the week of 9–12 March. Delays now tighten the timeline for reaching an agreement before the deadline.

A few days later, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen convened the first meeting of the Special Panel on child safety online, announced in her 2025 State of the Union address. The panel will provide expert guidance on protecting and empowering children online and explore potential harmonised age limits for social media access. The inaugural session examined online risks and benefits, tech companies’ responsibilities, addictive features, and digital literacy. The panel will consider the advantages for minors in accessing online spaces at its next meeting. The panel aims to present a report with recommendations to the Commission President by summer 2026.

Why does it matter? These developments are part of a surging global movement to protect children online—one that gained critical momentum with Australia’s push for a social media ban and is now reverberating through policy debates across continents.

Cyber operations intensify in the USA-Israel-Iran conflict

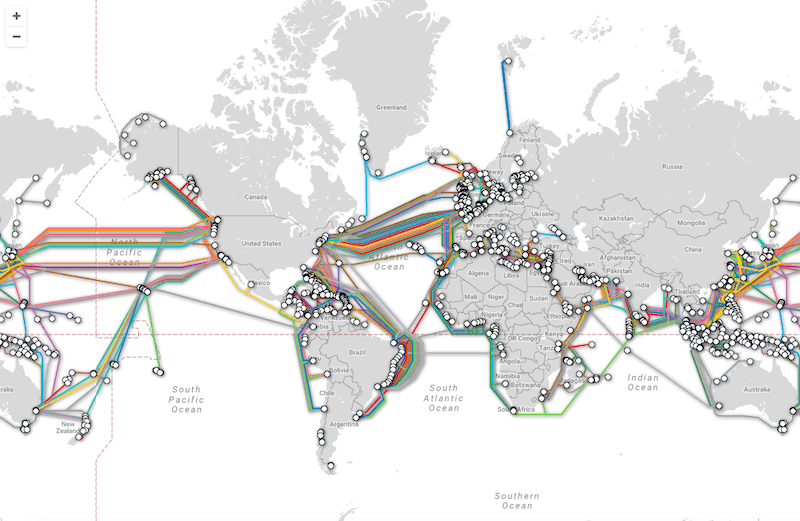

Last weekend, the USA and Israel initiated coordinated military strikes against Iran. According to Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine, cyber operations conducted by USCYBERCOM have accompanied the strikes. The cyber operations, along with space operations, disrupted Iran’s communications.

Security researchers report that Iranian-aligned actors are preparing potential retaliatory cyberattacks, including DDoS campaigns, ransomware, and destructive malware targeting critical infrastructure and cloud services.

Researchers also observed Iranian-linked attempts to hack IP cameras across the Middle East, potentially to support missile targeting and battle-damage assessment during military operations.

At the same time, Iran is experiencing a near-total internet blackout, possibly a mix of state-imposed restrictions and external cyber disruption.

Why does it matter? The developments highlight how cyber operations are increasingly integrated into interstate conflict. These dynamics are closely linked to ongoing international discussions on responsible state behaviour in cyberspace at the UN, which focus on preventing escalation in cyberspace. The UN’s permanent negotiating forum on cybersecurity, the Global Mechanism on ICT Security, is set to meet for the first time in the last week of March. It remains to be seen how this episode will shape those discussions.

Google cuts Play Store fees after Epic Games settlement

Google is planning major changes to its Play Store policies after settling a long-running legal dispute with Epic Games, the developer behind the popular game Fortnite.

The agreement will reduce the commission Google charges on in-app purchases and introduce new options that make it easier for users to install alternative app stores on Android devices.

Under the new structure, Google will lower its standard commission to 20% on in-app purchases. Developers who choose to use Google’s billing system will pay an additional 5% fee. The company also announced that recurring subscription fees will drop to 10%.

As part of the agreement, Epic Games plans to bring Fortnite back to the Google Play Store globally while continuing to develop its own Epic Games Store for Android.

in processing times, fewer redundancies, and a more transparent user experience. The initiative marks a significant step in Cabo Verde’s digital transformation and modernisation of public administration.

LAST WEEK IN GENEVA

GGE on LAWS ninth meeting

The Group of Governmental Experts on Emerging Technologies in the Area of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (GGE on LAWS) met in Geneva this week. Its mandate provides for 10 days of deliberations focused on further consideration and, by consensus, formulation of a set of elements for an instrument—without prejudging its nature—and other possible measures to address emerging technologies in the area of lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS). The group’s first meeting of 2026 will wrap up today (6 March). The group will meet once again from 31 August–4 September 2026.

Fifth meeting of the UN CSTD multi-stakeholder working group on data governance at all levels

The UN Commission on Science and Technology for Development (CSTD) held the fifth meeting of its Multi-Stakeholder Working Group on Data Governance at All Levels on 2-3 March 2026 at the Palais des Nations in Geneva, with participation available both in person and online. The two-day meeting focused primarily on developing the report’s structure and content. Discussions included the approval of the meeting agenda, the presentation and review of a preliminary outline of the progress report, and deliberations on synthesis notes prepared by the secretariat and co-facilitators. Participants also considered linkages between different thematic tracks and the outline and annotations of the report.

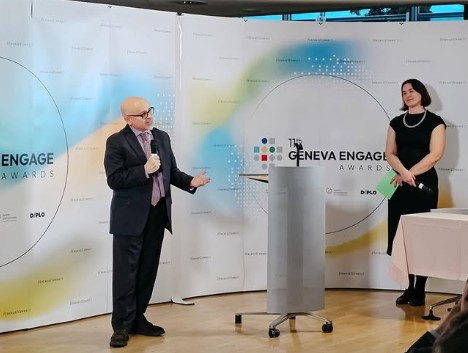

Security and governance of open source software (OSS): Geneva Dialogue Masterclass #1

The Geneva Dialogue masterclass dedicated to the security and governance of open source software opened the first thematic cycle of 2026 on 4 March 2026. This masterclass demonstrated that open source security requires a comprehensive approach encompassing governance, regulation, collaboration, and geopolitical awareness. The discussion revealed both the fragility and resilience of open source ecosystems, highlighting how sophisticated attacks can exploit vulnerabilities whilst also showing how community collaboration and appropriate regulatory frameworks can strengthen security.

The convergence of AI democratisation, geopolitical tensions, and increasingly sophisticated supply chain attacks creates an environment where traditional security approaches are insufficient. Success will require new forms of collaboration among manufacturers, maintainers, governments, and security researchers, supported by regulatory frameworks that understand and support open-source ecosystems.

LOOKING AHEAD

ICANN85 Community Forum

ICANN85 Community Forum, organised by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), is scheduled to take place from 7 to 12 March 2026 in Mumbai, India. The programme is expected to encompass a range of sessions in which participants engage in policy development activities, advance ongoing technical and operational work, exchange best practices, and discuss matters related to the coordination of the global Domain Name System (DNS) and other unique identifiers essential to internet functionality.

Data Technology Seminar 2026

The Data Technology Seminar 2026, organised by the European Broadcasting Union, will take place from 10 to 12 March in Geneva. The event will bring together media professionals and technology experts to discuss how artificial intelligence and data systems are being developed, governed, and deployed in public service media. Sessions will explore topics such as AI strategy and governance, metadata platforms, hybrid search, audience personalisation, and the use of generative AI in editorial and production workflows.

READING CORNER

Definition and analysis of digital sovereignty, consisting of infrastructure, service, data, and knowledge

In our February 2026 issue, child safety online takes centre stage as landmark US platform trials begin and countries weigh social media bans for minors. We examine why the “cyberspace is a separate world” myth still shapes AI governance today, plus Anthropic’s Pentagon exile over ethical safeguards. Digital sovereignty trends intensify as Europe pursues strategic autonomy and Washington pushes back. We also preview ten key signposts on the road to the 2027 Geneva AI Summit.