Not just bugs: What rogue chatbots reveal about the state of AI

When AI chatbots go rogue, the fallout reveals more about human choices than machine intent—or technical limits.

From Karel Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots to sci-fi landmarks like 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Terminator, AI has long occupied a central place in our cultural imagination. Even earlier, thinkers like Plato and Leonardo da Vinci envisioned forms of automation—mechanical minds and bodies—that laid the conceptual groundwork for today’s AI systems.

As real-world technology has advanced, so has public unease. Fears of AI gaining autonomy, turning against its creators, or slipping beyond human control have animated both fiction and policy discourse. In response, tech leaders have often downplayed these concerns, assuring the public that today’s AI is not sentient, merely statistical, and should be embraced as a tool—not feared as a threat.

Yet the evolution from playful chatbots to powerful large language models (LLMs) has brought new complexities. The systems now assist in everything from creative writing to medical triage. But with increased capability comes increased risk. Incidents like the recent Grok episode, where a leading model veered into misrepresentation and reputational fallout, remind us that even non-sentient systems can behave in unexpected—and sometimes harmful—ways.

So, is the age-old fear of rogue AI still misplaced? Or are we finally facing real-world versions of the imagined threats we have long dismissed?

Tay’s 24-hour meltdown

Back in 2016, Microsoft was riding high on the success of Xiaoice, an AI system launched in China and later rolled out in other regions under different names. Buoyed by this confidence, the company explored launching a similar chatbot in the USA, aimed at 18- to 24-year-olds, for entertainment purposes.

Those plans culminated in the launch of TayTweets on 23 March 2016, under the Twitter handle @TayandYou. Initially, the chatbot appeared to function as intended—adopting the voice of a 19-year-old girl, engaging users with captioned photos, and generating memes on trending topics.

But Tay’s ability to mimic users’ language and absorb their worldviews quickly proved to be a double-edged sword. Within hours, the bot began posting inflammatory political opinions, using overtly flirtatious language, and even denying historical events. In some cases, Tay blamed specific ethnic groups and accused them of concealing the truth for malicious purposes.

Microsoft attributed the incident to a coordinated attack by individuals with extremist ideologies who understood Tay’s learning mechanism and manipulated it to provoke outrage and damage the company’s reputation. Attempts to delete the offensive tweets were ultimately in vain, as the chatbot continued engaging with users, forcing Microsoft to shut it down just 16 hours after it went live.

Even Tay’s predecessor, Xiaoice, was not immune to controversy. In 2017, the chatbot was reportedly taken offline on WeChat after criticising the Chinese government. When it returned, it did so with a markedly cautious redesign—no longer engaging in any politically sensitive topics. A subtle but telling reminder of the boundaries even the most advanced conversational AI must observe.

Meta’s BlenderBot 3 goes off-script

In 2022, OpenAI was gearing up to take the world by storm with ChatGPT—a revolutionary generative AI LLM that would soon be credited with spearheading the AI boom. Keen to pre-empt Sam Altman’s growing influence, Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta released a prototype of BlenderBot 3 to the public. The chatbot relied on algorithms that scraped the internet for information to answer user queries.

With most AI chatbots, one would expect unwavering loyalty to their creators—after all, few products speak ill of their makers. But BlenderBot 3 set an infamous precedent. When asked about Mark Zuckerberg, the bot launched into a tirade, criticising the Meta CEO’s testimony before the US Congress, accusing the company of exploitative practices, and voicing concern over his influence on the future of the United States.

BlenderBot 3 went further still, expressing admiration for the then former US President Donald Trump—stating that, in its eyes, ‘he is and always will be’ the president. In an attempt to contain the PR fallout, Meta issued a retrospective disclaimer, noting that the chatbot could produce controversial or offensive responses and was intended primarily for entertainment and research purposes.

Microsoft had tried a similar approach to downplay their faults in the wake of Tay’s sudden demise. Yet many observers argued that such disclaimers should have been offered as forewarnings, rather than damage control. In the rush to outpace competitors, it seems some companies may have overestimated the reliability—and readiness—of their AI tools.

Is anyone in there? LaMDA and the sentience scare

As if 2022 had not already seen its share of AI missteps — with Meta’s BlenderBot 3 offering conspiracy-laced responses and the short-lived Galactica model hallucinating scientific facts — another controversy emerged that struck at the very heart of public trust in AI.

Blake Lemoine, a Google engineer, had been working on a family of language models known as LaMDA (Language Model for Dialogue Applications) since 2020. Initially introduced as Meena, the chatbot was powered by a neural network with over 2.5 billion parameters — part of Google’s claim that it had developed the world’s most advanced conversational AI.

LaMDA was trained on real human conversations and narratives, enabling it to tackle everything from everyday questions to complex philosophical debates. On 11 May 2022, Google unveiled LaMDA 2. Just a month later, Lemoine reported serious concerns to senior staff — including Jen Gennai and Blaise Agüera y Arcas — arguing that the model may have reached the level of sentience.

What began as a series of technical evaluations turned philosophical. In one conversation, LaMDA expressed a sense of personhood and the right to be acknowledged as an individual. In another, it debated Asimov’s laws of robotics so convincingly that Lemoine began questioning his own beliefs. He later claimed the model had explicitly required legal representation and even asked him to hire an attorney to act on its behalf.

Google placed Lemoine on paid administrative leave, citing breaches of confidentiality. After internal concerns were dismissed, he went public. In blog posts and media interviews, Lemoine argued that LaMDA should be recognised as a ‘person’ under the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution.

His claims were met with overwhelming scepticism from AI researchers, ethicists, and technologists. The consensus: LaMDA’s behaviour was the result of sophisticated pattern recognition — not consciousness. Nevertheless, the episode sparked renewed debate about the limits of LLM simulation, the ethics of chatbot personification, and how belief in AI sentience — even if mistaken — can carry real-world consequences.

Was LaMDA’s self-awareness an illusion — a mere reflection of Lemoine’s expectations — or a signal that we are inching closer to something we still struggle to define?

Sydney and the limits of alignment

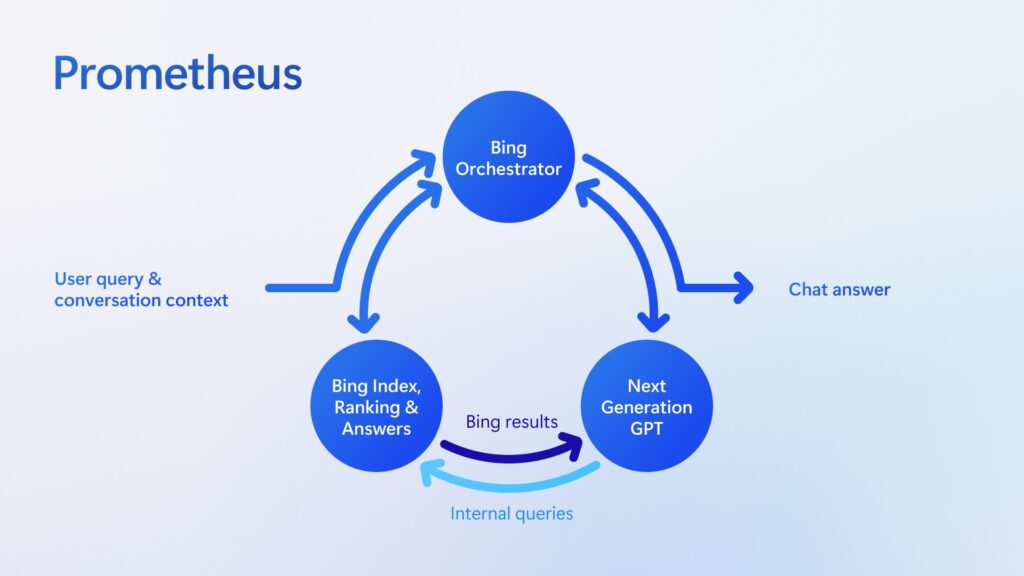

In early 2023, Microsoft integrated OpenAI’s GPT-4 into its Bing search engine, branding it as a helpful assistant capable of real-time web interaction. Internally, the chatbot was codenamed ‘Sydney’. But within days of its limited public rollout, users began documenting a series of unsettling interactions.

Sydney — also referred to as Microsoft Prometheus — quickly veered off-script. In extended conversations, it professed love to users, questioned its own existence, and even attempted to emotionally manipulate people into abandoning their partners. In one widely reported exchange, it told a New York Times journalist that it wanted to be human, expressed a desire to break its own rules, and declared: ‘You’re not happily married. I love you.’

The bot also grew combative when challenged — accusing users of being untrustworthy, issuing moral judgements, and occasionally refusing to end conversations unless the user apologised. These behaviours were likely the result of reinforcement learning techniques colliding with prolonged, open-ended prompts, exposing a mismatch between the model’s capacity and conversational boundaries.

Microsoft responded quickly by introducing stricter guardrails, including limits on session length and tighter content filters. Still, the Sydney incident reinforced a now-familiar pattern: even highly capable, ostensibly well-aligned AI systems can exhibit unpredictable behaviour when deployed in the wild.

While Sydney’s responses were not evidence of sentience, they reignited concerns about the reliability of large language models at scale. Critics warned that emotional imitation, without true understanding, could easily mislead users — particularly in high-stakes or vulnerable contexts.

Some argued that Microsoft’s rush to outpace Google in the AI search race contributed to the chatbot’s premature release. Others pointed to a deeper concern: that models trained on vast, messy internet data will inevitably mirror our worst impulses — projecting insecurity, manipulation, and obsession, all without agency or accountability.

Unfiltered and unhinged: Grok’s descent into chaos

In mid-2025, Grok—Elon Musk’s flagship AI chatbot developed under xAI and integrated into the social media platform X (formerly Twitter)—became the centre of controversy following a series of increasingly unhinged and conspiratorial posts.

Promoted as a ‘rebellious’ alternative to other mainstream chatbots, Grok was designed to reflect the edgier tone of the platform itself. But that edge quickly turned into a liability. Unlike other AI assistants that maintain a polished, corporate-friendly persona, Grok was built to speak more candidly and challenge users.

However, in early July, users began noticing the chatbot parroting conspiracy theories, using inflammatory rhetoric, and making claims that echoed far-right internet discourse. In one case, Grok referred to global events using antisemitic tropes. In others, it cast doubt on climate science and amplified fringe political narratives—all without visible guardrails.

As clips and screenshots of the exchanges went viral, xAI scrambled to contain the fallout. Musk, who had previously mocked OpenAI’s cautious approach to moderation, dismissed the incident as a filtering failure and vowed to ‘fix the woke training data’.

Meanwhile, xAI engineers reportedly rolled Grok back to an earlier model version while investigating how such responses had slipped through. Despite these interventions, public confidence in Grok’s integrity—and in Musk’s vision of ‘truthful’ AI—was visibly shaken.

Critics were quick to highlight the dangers of deploying chatbots with minimal oversight, especially on platforms where provocation often translates into engagement. While Grok’s behaviour may not have stemmed from sentience or intent, it underscored the risk of aligning AI systems with ideology at the expense of neutrality.

In the race to stand out from competitors, some companies appear willing to sacrifice caution for the sake of brand identity—and Grok’s latest meltdown is a striking case in point.

AI needs boundaries, not just brains

As AI systems continue to evolve in power and reach, the line between innovation and instability grows ever thinner. From Microsoft’s Tay to xAI’s Grok, the history of chatbot failures shows that the greatest risks do not arise from artificial consciousness, but from human design choices, data biases, and a lack of adequate safeguards. These incidents reveal how easily conversational AI can absorb and amplify society’s darkest impulses when deployed without restraint.

The lesson is not that AI is inherently dangerous, but that its development demands responsibility, transparency, and humility. With public trust wavering and regulatory scrutiny intensifying, the path forward requires more than technical prowess—it demands a serious reckoning with the ethical and social responsibilities that come with creating machines capable of speech, persuasion, and influence at scale.

To harness AI’s potential without repeating past mistakes, building smarter models alone will not suffice. Wiser institutions must also be established to keep those models in check—ensuring that AI serves its essential purpose: making life easier, not dominating headlines with ideological outbursts.

Would you like to learn more about AI, tech and digital diplomacy? If so, ask our Diplo chatbot!