Inclusive finance

Inclusive finance ‘strives to enhance access to and usage of financial services for both individuals and micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs)’. Inclusive finance is therefore concerned with efforts towards financial inclusion, namely ‘the universal access to and usage of a wide range of affordable financial services, provided by a variety of sound, responsible, and sustainable financial service providers.’

Financial inclusion gained global prominence in 2006 when Muhammad Yunus won the Nobel Peace Prize for pioneering microfinance. Yunus described his vision as creating banks for the poor, who were largely left out of financial systems. The idea of microfinance was revolutionary then, but today it has been mainstreamed into initiatives for the reduction of poverty. For example, the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) have identified increased access to financial services for all as a means to to accelerate development.

The unbanked

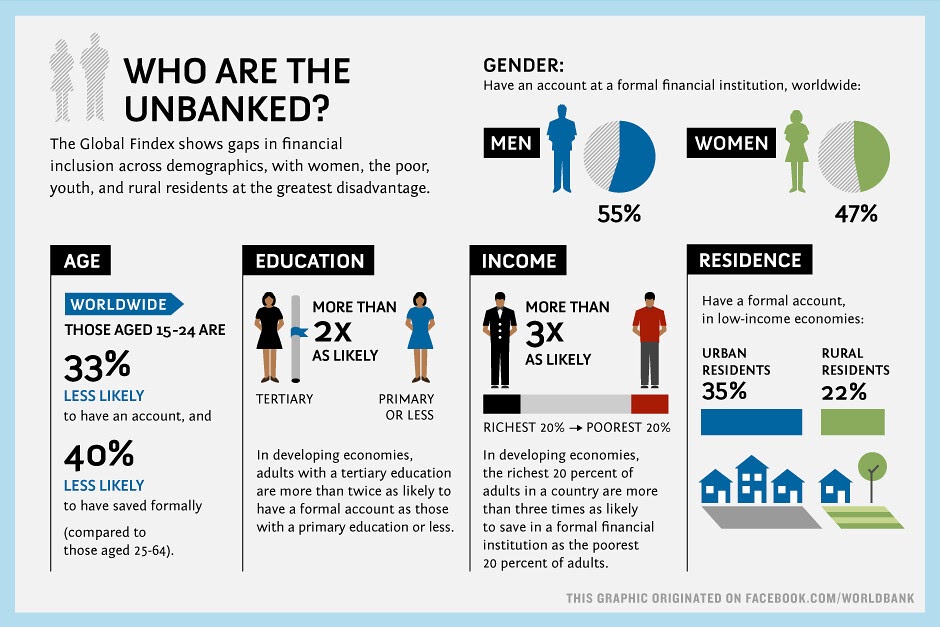

In 2017, Findex data showed that 1.7 billion adults were still unbanked, meaning they do not have bank accounts. Of these unbanked, people from rural areas, youth, and women were disproportionately affected.

More unbanked people are also found in developing economies, where they lack banking services not only because of poverty, but also due to costs, travel, and associated paperwork. The World Bank Group (WBG) estimated in April 2020 that about 65% of adults in the world’s poorest economies lack access to even the most basic transaction account that would allow them to send and receive payments more safely and efficiently. Financial technology (fintech) has been identified as a way through which unbanked people can access financial services.

Application of digital technologies and inclusive finance

The application of digital technologies to financial systems has greatly advanced financial inclusion. In the global south, millions of people accessed their first financial services through mobile money – a novel concept where money is held in electronic form on mobile phones. The success of mobile money in inclusive finance has led to several spin-offs; the fastest growing trend being mobile money credit or digital lending.

Digital lending enables people to access financing without having to make a trip to a physical institution in order to apply. Most digital lending is done through apps that can be downloaded on smartphones or Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD). The borrower is not required to have collateral in order to access credit facilities.

Such lending takes many forms, from micro loans and digital savings to micro overdraft facilities for services such as paying for electricity. An essential feature of digital lending is the digital profiling of a prospective borrower. For one to get credit, the lender first accesses their mobile phone and analyses the borrower’s digital behavior. This includes analysing information such as the person’s contacts, frequency of calls, location, spending habits, the kind of apps they download, the purchases they make, and so on to determine their credit-worthiness.

Some digital lending apps extend the loan limit for borrowers who have had a good credit history on that app, which is expected to increase opportunities for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Examples of these apps include Tala and Branch international, which are present in several global south countries. There are also numerous apps as well as simplified banking services offering micro personal and business loans that one can repay within short periods of between one day and six months.

Going forward, inclusive finance is becoming more interlinked with legal digital identities. Development partners are rolling out programmes on digital identities with, among others, the objective of providing finance to persons who need it. The World Bank’s (WB) Identity for Development (ID4D) project has been offering technical assistance to low and medium income countries that are implementing digital identification systems.

Some applications for digital ID include cash transfers for social support programmes for the needy and vulnerable, as well as digital loans. Biometric identification has been widely adopted to cater for (digitally) illiterate populations. The World Economic Forum (WEF) also considers digital ID key to financial inclusion.

Read more about digital identities.

Both development partners and industry associations are incorporating financial inclusion into their development strategies. The WBG is supporting low and middle income countries to roll out digital IDs that support financial technology. The UN has a taskforce on harnessing financial technology for the financing of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). A UN interagency task force on financing for development is implementing the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, which contains policy commitments on achieving financial inclusion. The global mobile industry association, Groupe Speciale Mobile Association (GSMA), spearheads research on andl certification of mobile money. The G20 has developed the G20 High-Level Principles for Digital Financial Inclusion indicators, while the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has adopted a financial inclusion strategy that takes a private sector led approach.

Challenges and risks of applying digital technologies to financial systems

The intersection of finance and digital technologies is not without challenges. From a regulatory perspective, it requires collaboration between financial, communications, and competition regulators. This also comes with the risk of overregulation or the stifling of innovation, particularly as service providers experiment with financial models for including the unbanked.

However, the main critiques to financial inclusion through digital technologies is that credit models such as digital lending result in the growth of lending companies while borrowers remain over-indebted or trapped in debt for non-performing loans. Over-indebted borrowers are unable to repay their loans on time and they often have to borrow from other apps in order to meet their obligations. In addition to greater financial growth, these lending companies gain data that gives them a competitive advantage.

The use of big data and artificial intelligence (AI) to provide financial services heightens the risk of intrusion into privacy. For example, many countries do not have regulations on protection of personal data used for digital lending apps. Lending apps therefore set the rules on issues such as what data to access and when to dispose of it.

Read more about artificial intelligence.

Automated decision making is another challenge. Financial decisions can be made from an analysis of a person’s online activity, sometimes without the person’s knowledge. The balance between inclusive finance and protection of personal autonomy is therefore a policy consideration for financial inclusion.

In addition, as with other industries that rely on big data, there is a tendency towards creating huge technology corporations that become dominant service providers. In Kenya, for example, concerns are being raised about the crippling effect of outages on the popular mobile money service M-Pesa.

As more business models for inclusive finance emerge, countries are also coming up with regulations to meet the challenges that come with such models. Some of these include requiring inclusive finance actors to be locally based or to deposit commitment fees within the country, as well as requirements for licensing, taxation, and data protection.