Net neutrality and zero-rating

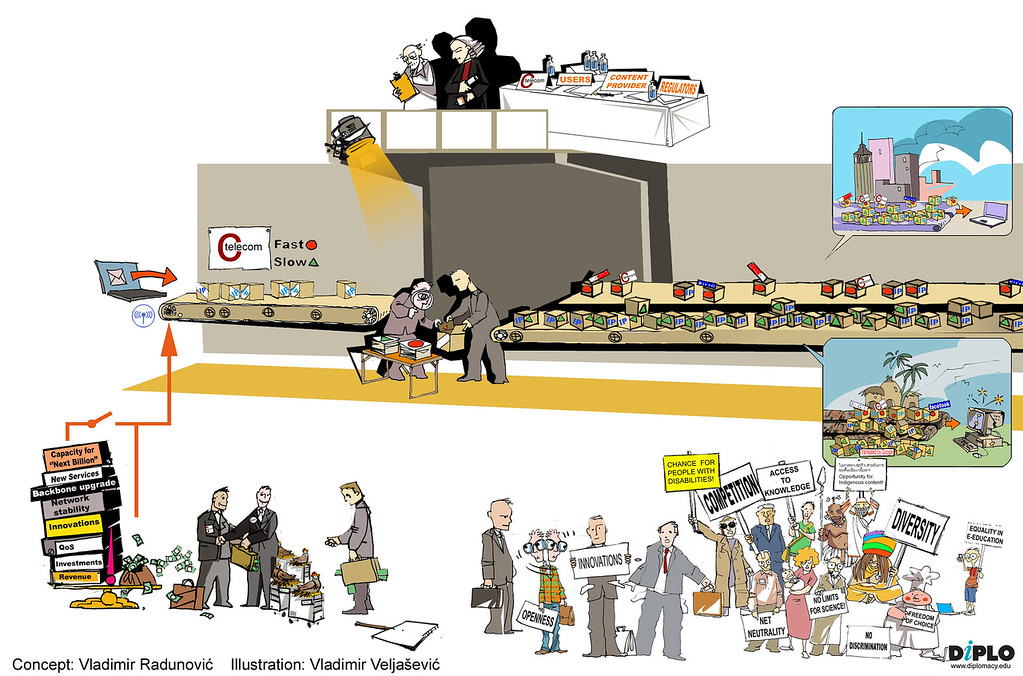

Net neutrality is the principle that internet operators should treat internet content equally. Thus, for instance, providers such as Verizon, Swisscom, NTT, and others should not throttle Skype or Netflix to encourage customers to purchase packages with faster speeds. Zero-rating is similarly frowned upon; such services allow unlimited (free) use of specific applications or services, without the data counting towards a subscriber’s data threshold.

The internet’s success lies in its design, which is based on the principle of net neutrality. From the outset, the flow of all the content on the internet was treated without discrimination. New entrepreneurs did not need permission or market power to innovate on the internet.

With the development of new digital services, especially the ones consuming large amounts of bandwidth such as high-quality video streaming, some internet operators started prioritising certain traffic – such as their own services or the services of their business partners – based on their business needs and plans. They justify this discriminatory approach by citing the need to raise funds to further invest in their networks. Net neutrality proponents strongly fight back such plans arguing that this could limit open access to information and online freedoms, and stifle online innovation.

Are all bits created equal? Since the early days of dial-up modem connection to the internet, network traffic management has been used to prioritise certain traffic. For example, internet traffic carrying Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services (such as Skype) should have priority over traffic carrying a simple email: While we can hear delays in Skype voice chat, we will not notice minor delays in an email exchange.

With the continuously increasing demand for high bandwidth – prompted by over-the-top (OTT) services such as VoIP and movie streaming – traffic management has become increasingly sophisticated in routing internet traffic in the most optimal way for providing quality of service, preventing congestion, and eliminating latency and jitter.

Initially, net neutrality purists argued that ‘all bits are created equal’ and that all internet traffic must be treated equally. Telecoms and ISPs challenged this view, arguing that users should have equal access to internet services and if this were to happen, internet traffic could not be treated equally. If both video and email traffic were treated equally, users would not have good video-stream reception. Eventually, this rationale was no longer questioned.

The emergence of OTT services

In the past few decades, network operators adapted their business models to introduce their own OTT services such as video-on-demand or IPTV (television via the internet), in addition to providing internet access. They now compete not only with their counterparts for providing cheaper, faster, and better quality internet connections, but also with OTT service providers.

What are the consequences of these new services? First, in this new competitive environment, operators are often tempted to prioritise packages, for instance, by slowing down or banning the flow of data packages from a competing company, while giving priority to data packages of its own in-house service.

Second, operators argue that the demand for more bandwidth – spurred mostly by OTT services – requires them to invest more in basic infrastructure. In their view, since OTT service providers are the ones benefiting the most from the improved infrastructure, a multi-tiered network policy model that requires providers to contribute financially would guarantee the necessary quality of service for OTT consumers.

Zero-rating services

The controversial zero-rating services are one of the industry’s main attempts to increase revenues through new business models. Offered mainly to customers by mobile telecom providers, these services allow unlimited (free) use of specific applications or services, without this use counting towards a subscriber’s data threshold. In some cases, users are allowed access even without a data plan.

One of the main arguments in favour of zero-rating is that it lowers the cost of access to online information (when offered as part of a data plan), and gives access to some online information to users who cannot afford a data plan (when access is free of charge). Supporters consider access to some information is preferable to no access at all.

Opponents argue that zero-rating prioritises certain services over others, and therefore challenges the net neutrality principle while harming market competition and innovation. Some also express concern over the implications that zero-rating could have on users’ human rights, in that such services can conflict with a user’s right to information.

Debates on zero-rating became more intensive following Facebook’s introduction of Free Basics in 2014. Offered by Facebook and its partners (the partnership is called Internet.org) in several developing and less developed countries, the service allows users of mobile communications to access applications such as Wikipedia and AccuWeather – in addition to Facebook – without incurring data charges. Debates led to the suspension of the service in some of the countries where it had been previously introduced, such as India and Egypt.

Regulating net neutrality: Policy approaches

Why regulate? A breach of net neutrality principles could harm competition as it would lead to discrimination against other (usually smaller) service providers, and would stifle innovation. The counter-argument is that regulation could also discourage large companies from investing in the infrastructure.

The consequences of breaching net neutrality principles are not only economic. The Internet has become one of the key pillars of modern society, and is linked to basic human rights, including access to information, health, education, and freedom of expression. Endangering the openness of the Internet could therefore impact fundamental rights. Whether access to some information is preferable to no access at all is still highly debated.

In addition, the ability to manage network traffic based on origin or destination or on service or content could give authorities the opportunity to filter Internet traffic with objectionable or sensitive content in relation to the country’s political, ideological, religious, cultural, or other values. This opens up possibilities for political censorship through Internet traffic management.

How have countries been regulating net neutrality? One of the major challenges that regulators have always faced is whether to act preemptively (ex-ante) in order to prevent possible breaches of the net neutrality principle, or to respond based on precedents (ex-post) once (and if) the breach occurs.

Another challenge is whether the issue should be dealt with hard law (encoding the principles into legislation) or soft law (through guidelines and policies).

In the USA, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) adopted a set of rules to safeguard the principles of net neutrality. Entered into force in June 2015, the rules banned three practices that are seen as harming an open Internet: blocking of lawful content, applications, services or devices; impairing or degrading lawful internet traffic on the basis of content, application, or service (throttling); and, the paid prioritisation of certain content, applications, or services. In 2018, under a new administration, the FCC repealed the 2015 rules. The FCC’s Restoring Internet Freedom Order took effect in June 2018, restoring the classification of broadband Internet access service as a lightly-regulated information service. Following this decision, which was met by heavy criticism, many US states – including Washington, Oregon, and Maine – have started enacting their own net neutrality rules.

In the EU, Regulation 2015/2120 obliges providers of Internet access services to treat all traffic equally when providing Internet access services. This means treating all traffic without discrimination, restriction, or interference, and irrespective of the sender and receiver, the content accessed or distributed, the applications or services used or provided, or the terminal equipment used. The regulation also deals with specialised services, allowing operators to offer ‘services other than Internet access services which are optimised for specific content, applications, or services, or a combination thereof, where the optimisation is necessary in order to meet requirements of the content, applications, or services for a specific level of quality’. The regulation was followed by a set of implementation guidelines, issued by the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC).

Brazil, Chile, Slovenia, and the Netherlands protect net neutrality through national legislation. Norway chose a soft-law approach, with the national regulatory authority issuing a set of guidelines for network neutrality (drafted in collaboration with various industry players and consumer protection agencies).