ΑΙ has reshaped almost every domain of digital life, from creativity and productivity to surveillance and governance.

One of the most controversial and ethically fraught areas of AI deployment involves pornography, particularly where generative systems are used to create, manipulate, or simulate sexual content involving real individuals without consent.

What was once a marginal issue confined to niche online forums has evolved into a global policy concern, driven by the rapid spread of AI-powered nudity applications, deepfake pornography, and image-editing tools integrated into mainstream platforms.

Recent controversies surrounding AI-powered nudity apps and the image-generation capabilities of Elon Musk’s Grok have accelerated public debate and regulatory scrutiny.

Governments, regulators, and civil society organisations increasingly treat AI-generated sexual content not as a matter of taste or morality, but as an issue of digital harm, gender-based violence, child safety, and fundamental rights.

Legislative initiatives such as the US Take It Down Act illustrate a broader shift toward recognising non-consensual synthetic sexual content as a distinct and urgent category of abuse.

Our analysis examines how AI has transformed pornography, why AI-generated nudity represents a qualitative break from earlier forms of online sexual content, and how governments worldwide are attempting to respond.

It also explores the limits of current legal frameworks and the broader societal implications of delegating sexual representation to machines.

From online pornography to synthetic sexuality

Pornography has long been intertwined with technological change. From photography and film to VHS tapes, DVDs, and streaming platforms, sexual content has often been among the earliest adopters of new media technologies.

The transition from traditional pornography to AI-generated sexual content, however, marks a deeper shift than earlier format changes.

Conventional online pornography relies on human performers, production processes, and contractual relationships, even where exploitation or coercion exists. AI-generated pornography, instead of depicting real sexual acts, simulates them using algorithmic inference.

Faces, bodies, voices, and identities can be reconstructed or fabricated at scale, often without the knowledge or consent of the individuals whose likenesses are used.

AI nudity apps exemplify such a transformation. These tools allow users to upload images of real people and generate artificial nude versions, frequently marketed as entertainment or novelty applications.

The underlying technology relies on diffusion models trained on vast datasets of human bodies and sexual imagery, enabling increasingly realistic outputs. Unlike traditional pornography, the subject of the image may never have participated in any sexual act, yet the resulting content can be indistinguishable from authentic photography.

Such a transformation carries profound ethical implications. Instead of consuming representations of consensual adult sexuality, users often engage in simulations of sexual advances on real individuals who have not consented to being sexualised.

Such a distinction between fantasy and violation becomes blurred, particularly when such content is shared publicly or used for harassment.

AI nudity apps and the normalisation of non-consensual sexual content

The recent proliferation of AI nudity applications has intensified concerns around consent and harm. These apps are frequently marketed through euphemistic language, emphasising humour, experimentation, or artistic exploration instead of sexual exploitation.

Their core functionality, however, centres on digitally removing clothing from images of real people.

Regulators and advocacy groups increasingly argue that such tools normalise a culture in which consent is irrelevant. The ability to undress someone digitally, without personal involvement, reflects a broader pattern of technological power asymmetry, where the subject of the image lacks meaningful control over how personal likeness is used.

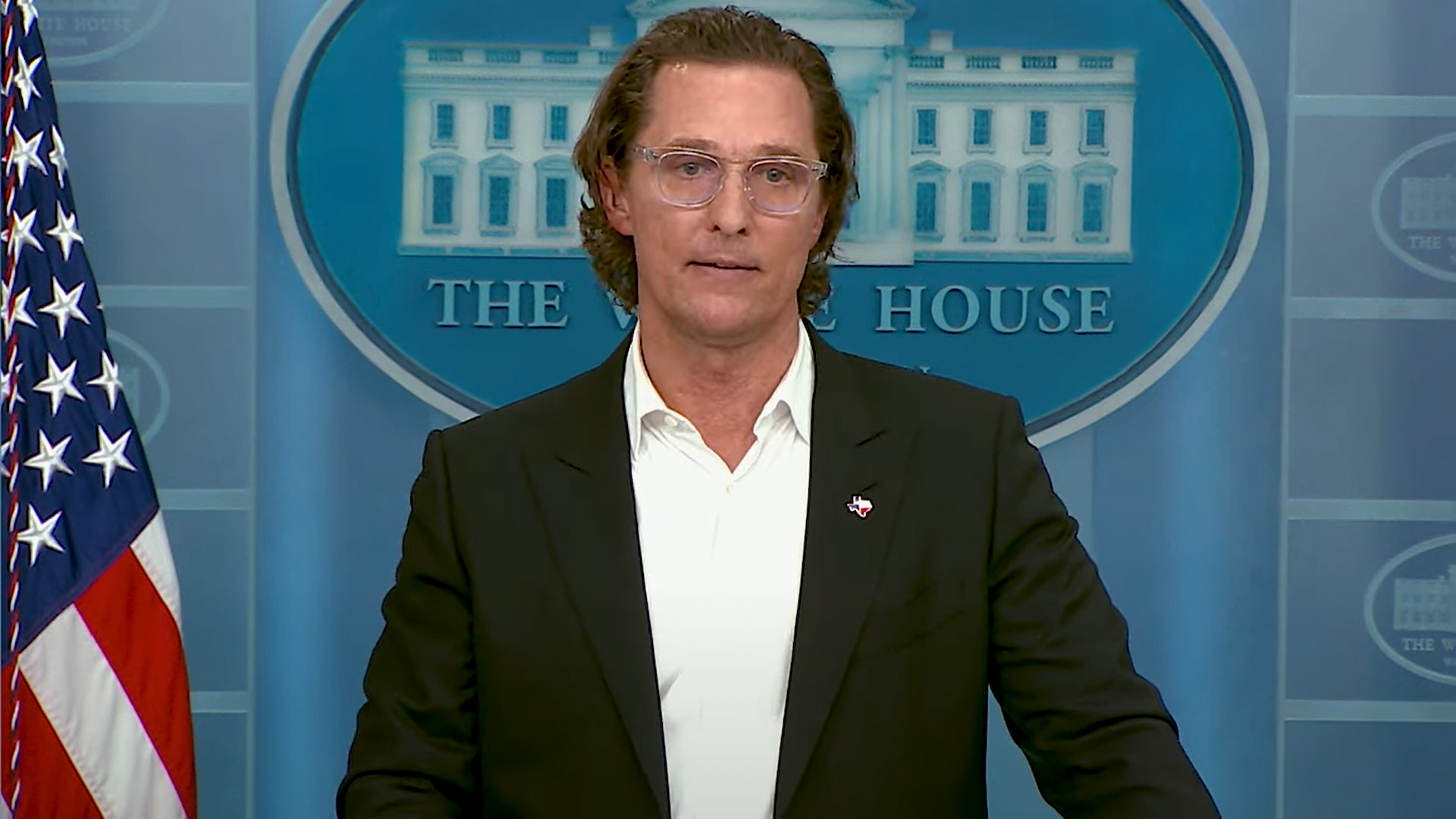

The ongoing Grok controversy illustrates how quickly the associated harms can scale when AI tools are embedded within major platforms. Reports that Grok can generate or modify images of women and children in sexualised ways have triggered backlash from governments, regulators, and victims’ rights organisations.

Even where companies claim that safeguards are in place, the repeated emergence of abusive outputs suggests systemic design failures rather than isolated misuse.

What distinguishes AI-generated sexual content from earlier forms of online abuse lies not only in realism but also in replicability. Once an image or model exists, reproduction can occur endlessly, with the content shared across jurisdictions and recontextualised in new forms. Victims often face a permanent loss of control over digital identity, with limited avenues for redress.

Gendered harm and child protection

The impact of AI-generated pornography remains unevenly distributed. Research and reporting consistently show that women and girls are disproportionately targeted by non-consensual synthetic sexual content.

Public figures, journalists, politicians, and private individuals alike have found themselves subjected to sexualised deepfakes designed to humiliate, intimidate, or silence them.

Children face even greater risk. AI tools capable of generating nudified or sexualised images of minors raise alarm across legal and ethical frameworks. Even where no real child experiences physical abuse during content creation, the resulting imagery may still constitute child sexual abuse material under many legal definitions.

The existence of such content contributes to harmful sexualisation and may fuel exploitative behaviour. AI complicates traditional child protection frameworks because the abuse occurs at the level of representation, not physical contact.

Legal systems built around evidentiary standards tied to real-world acts struggle to categorise synthetic material, particularly where perpetrators argue that no real person suffered harm during production.

Regulators increasingly reject such reasoning, recognising that harm arises through exposure, distribution, and psychological impact rather than physical contact alone.

Technology companies have historically relied on self-regulation to address harmful content. In the context of AI-generated pornography, such an approach has demonstrated clear limitations.

Platform policies banning non-consensual sexual content often lag behind technological capabilities, while enforcement remains inconsistent and opaque.

The Grok case highlights these challenges. Even where companies announce restrictions or safeguards, questions remain regarding enforcement, detection accuracy, and accountability.

AI systems struggle to reliably determine whether an image depicts a real person, whether consent exists, or whether local laws apply. Technical uncertainty frequently serves as justification for delayed action.

Commercial incentives further complicate moderation efforts. AI image tools drive user engagement, subscriptions, and publicity. Restricting capabilities may conflict with business objectives, particularly in competitive markets.

As a result, companies tend to act only after public backlash or regulatory intervention, instead of proactively addressing foreseeable harm.

Such patterns have contributed to growing calls for legally enforceable obligations rather than voluntary guidelines. Regulators increasingly argue that platforms deploying generative AI systems should bear responsibility for foreseeable misuse, particularly where sexual harm is involved.

Legal responses and the emergence of targeted legislation

Governments worldwide are beginning to address AI-generated pornography through a combination of existing laws and new legislative initiatives. The Take It Down Act represents one of the most prominent attempts to directly confront non-consensual intimate imagery, including AI-generated content.

The Act strengthens platforms’ obligations to remove intimate images shared without consent, regardless of whether the content is authentic or synthetic. Victims’ rights to request takedowns are expanded, while procedural barriers that previously left individuals navigating complex reporting systems are reduced.

Crucially, the law recognises that harm does not depend on image authenticity, but on the impact experienced by the individual depicted.

Within the EU, debates around AI nudity apps intersect with the AI Act and the Digital Services Act (DSA). While the AI Act categorises certain uses of AI as prohibited or high-risk, lawmakers continue to question whether nudity applications fall clearly within existing bans.

Calls to explicitly prohibit AI-powered nudity tools reflect concern that legal ambiguity creates enforcement gaps.

Other jurisdictions, including Australia, the UK, and parts of Southeast Asia, are exploring regulatory approaches combining platform obligations, criminal penalties, and child protection frameworks.

Such efforts signal a growing international consensus that AI-generated sexual abuse requires specific legal recognition rather than fragmented treatment.

Enforcement challenges and jurisdictional fragmentation

Despite legislative progress, enforcement remains a significant challenge. AI-generated pornography operates inherently across borders. Applications may be developed in one country, hosted in another, and used globally. Content can be shared instantly across platforms, subject to different legal regimes.

Jurisdictional fragmentation complicates takedown requests and criminal investigations. Victims often face complex reporting systems, language barriers, and inconsistent legal standards. Even where a platform complies with local law in one jurisdiction, identical material may remain accessible elsewhere.

Technical enforcement presents additional difficulties. Automated detection systems struggle to distinguish consensual adult content from non-consensual synthetic imagery. Over-reliance on automation risks false positives and censorship, while under-enforcement leaves victims unprotected.

Balancing accuracy, privacy, and freedom of expression remains unresolved.

Broader societal implications

Beyond legal and technical concerns, AI-generated pornography raises deeper questions about sexuality, power, and digital identity.

The ability to fabricate sexual representations of others undermines traditional understandings of bodily autonomy and consent. Sexual imagery becomes detached from lived experience, transformed into manipulable data.

Such shifts risk normalising the perception of individuals as visual assets rather than autonomous subjects. When sexual access can be simulated without consent, the social meaning of consent itself may weaken.

Critics argue that such technologies reinforce misogynistic and exploitative norms, particularly where women’s bodies are treated as endlessly modifiable digital material.

At the same time, defenders of generative AI warn of moral panic and excessive regulation. Arguments persist that not all AI-generated sexual content is harmful, particularly where fictional or consenting adult representations are involved.

The central challenge lies in distinguishing legitimate creative expression from abuse without enabling exploitative practices.

In conclusion, we must admit that AI has fundamentally altered the landscape of pornography, transforming sexual representation into a synthetic, scalable, and increasingly detached process.

AI nudity apps and controversies surrounding AI tools demonstrate how existing social norms and legal frameworks remain poorly equipped to address non-consensual synthetic sexual content.

Global responses indicate a growing recognition that AI-generated pornography constitutes a distinct category of digital harm. Regulation alone, however, will not resolve the issue.

Effective responses require legal clarity, platform accountability, technical safeguards, and cultural change, especially with the help of the educational system.

As AI systems become more powerful and accessible, societies must confront difficult questions about consent, identity, and responsibility in the digital age.

The challenge lies not merely in restricting technology, but in defining ethical boundaries that protect our human dignity while preserving legitimate innovation.

In the days, weeks or months ahead, decisions taken by governments, platforms, and communities will shape the future relationship between AI and our precious human autonomy.

Would you like to learn more about AI, tech and digital diplomacy? If so, ask our Diplo chatbot!