What impact does tracking have?

In the digital world, tracking occurs through digital signals sent from one computer to a server, and from a server to an organisation. Almost immediately, a profile of a user can be created. The information can be leveraged to send personalised advertisements for products and services consumers are interested in, but it can also classify people into categories to send them advertisements to steer them in a certain direction, for example, politically (2024 Romanian election, Cambridge Analytica Scandal skewing the 2016 Brexit referendum and 2016 US Elections).

Digital tracking can be carried out with minimal costs, rapid execution and the capacity to reach hundreds of thousands of users simultaneously. These methods require either technical skills (such as coding) or access to platforms that automate tracking.

Image taken from the Internet Archive

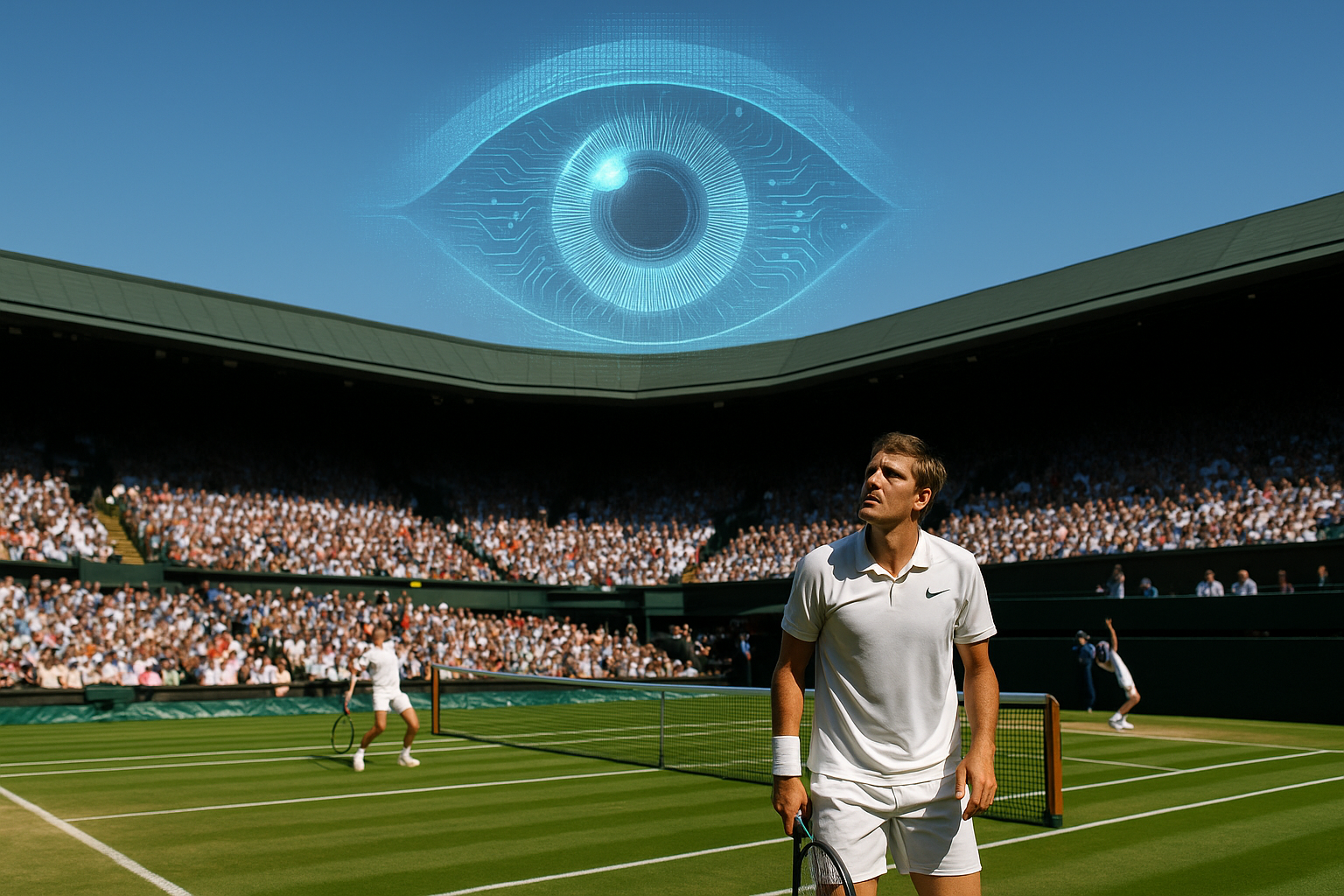

This phenomenon has been well documented and likened to George Orwell’s 1984, in which the people of Oceania are subject to constant surveillance by ‘Big Brother’ and institutions of control; the Ministry of Truth (propaganda), Peace (military control), Love (torture and forced loyalty) and Plenty (manufactured prosperity).

How are we tracked? The case of cookies and device fingerprinting

- Cookies

Cookies are small, unique text files placed on a user’s device by their web browser at the request of a website. When a user visits a website, the server can instruct the browser to create or update a cookie. These cookies are then sent back to the server with each subsequent request to the same website, allowing the server to recognise and remember certain information (login status, preferences, or tracking data).

If a user visits multiple websites about a specific topic, that pattern can be collected and sold to advertisers targeting that interest. This applies to all forms of advertising, not just commercial but also political and ideological influence.

- Device fingerprinting

Device fingerprinting involves generating a unique identifier using a device’s hardware and software characteristics. Types include browser fingerprinting, mobile fingerprinting, desktop fingerprinting, and cross-device tracking. To assess how unique a browser is, users can test their setup via the Cover Your Tracks tool by the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Different information will be collected, such as your operating system, language version, keyboard settings, screen resolution, font used, device make and model and more. The more data points collected, the more unique an individual’s device will be.

Image taken from Lan Sweeper

A common reason to use device fingerprinting is for advertising. Since each individual has a unique identifier, advertisers can distinguish individuals from one another and see which websites they visit based on past collected data.

Similar to cookies, device fingerprinting is not purely about advertising, as it has some legitimate security purposes. Device fingerprinting, as it creates a unique ID of a device, allows websites to recognise a user’s device. This is useful to combat fraud. For instance, if a known device suddenly logs in from an unknown fingerprint, fraud detection mechanisms may flag and block the login attempt.

Legal considerations

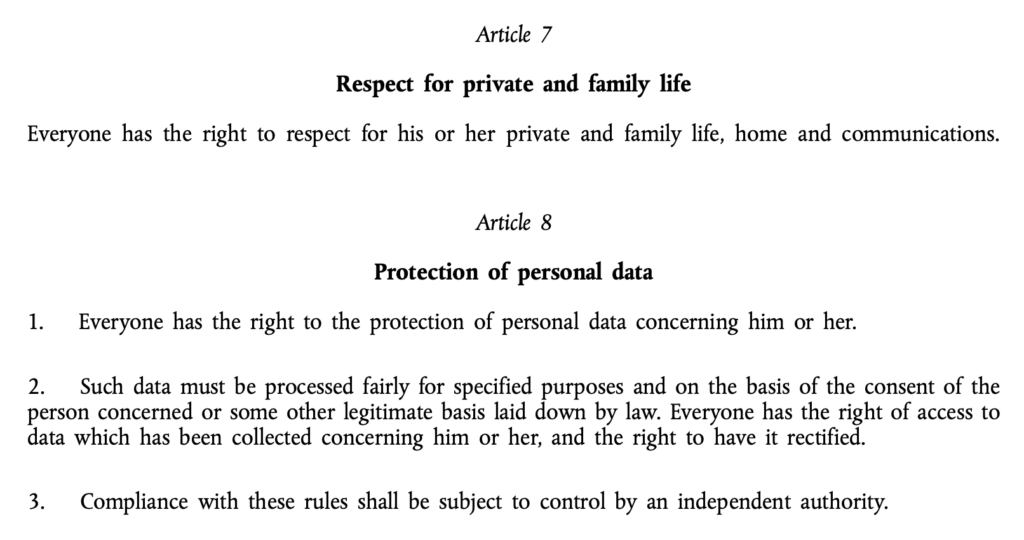

Apart from societal impacts, there are legal considerations to be made, specifically concerning fundamental rights. In the EU and Europe, Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights are what give rise to the protection of personal data in the first place. They form the legal bedrock of digital privacy legislation, such as the GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive. Stemming from the GDPR, there is a protection against unlawful, unfair and opaque processing of personal data.

Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights

For tracking to be carried out lawfully, one of the six legal bases of the GDPR must be relied upon. In this case, tracking is usually only lawful if the legal basis of consent is relied upon (Article 6(1)(a) GDPR, which stems from Article 5(1) of the ePrivacy Directive).

Other legal bases, such as the legitimate interest of a business, may allow for limited analytical cookies to be placed, of which the cookies referred to in this analysis are not.

Regardless of this, to obtain consent, website visitors must ensure that consent is collected prior to processing occurring, freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous. In most cases of website tracking, consent is not collected prior to processing.

In practice, this means that before a consent request is fulfilled by a website visitor, cookies are placed on the user’s device. There are additional concerns about consent not being informed, as users do not know what processing personal data to enable tracking entails.

Moreover, consent is not specific to what is necessary to the processing, given that processing occurs for broad and unspecified reasons, such as improving visitor experience and understanding the website better, and those explanations are generic and broad.

Further, tracking is typically unfair as users do not expect to be tracked across sites or have digital profiles made about themselves based on website visits. Tracking is also opaque, as users do not understand how tracking occurs. Website owners state that tracking occurs with a lack of explanation on how it occurs in the first place. Users do not know for how long it occurs, what personal data is being used to track or how it benefits website owners.

Can we refuse tracking

In theory, it is possible to prevent tracking from the get-go. This can be done by refusing to give consent when tracking occurs. However, in practice, refusing consent can still lead to tracking. Outlined below are two concrete examples of this happening daily.

- Cookies

This increases user frustration as they are given a choice that is non-existent. This occurs as non-essential cookies, which can be refused, are lumped together with essential cookies, which cannot be refused. Therefore, when refusing consent to non-essential cookies, not all are refused, as some are mislabelled.

Another reason for this occurrence is that cookies are placed before consent is sought. Often, website owners outsource cookie banner compliance to more experienced companies. These websites use consent management platforms (CMPs) such as Cookiebot by Usercentrics or One Trust.

When verifying when cookies are placed via these CMPs, the option to load cookies after consent is sought needs to be manually selected. Therefore, website owners need to have knowledge about consent requirements to understand that cookies are not to be placed prior to consent being sought.

Image taken from Buddy Company

- Google Consent Mode

Another example is related to Google Consent Mode (GCM). GCM is relevant to mention here as Google is the most common third-party tracker on the web, thus the most likely tracker users will encounter. They have a vast array of trackers ranging from statistics, analytics, preferences, marketing and more. GCM essentially creates a path for website analytics to occur despite consent being refused. This occurs as GCM claims that it can send cookieless ping signals to user devices to know how many users have viewed a website, clicked on a page, searched a term, etc.

This is a novel solution Google is presenting, and it claims to be privacy-friendly, as no cookies are required for this to occur. However, a study on tags, specifically GCM tags, found that GCM is not privacy-friendly and infringes the GDPR. The study found that Google still collects personal data in these ‘cookieless ping signals’ such as user language, screen resolution, computer architecture, user agent string, operating system and its version, complete web page URL and search keywords. Since this data is collected and processed despite the user refusing consent, there are undoubtedly legal issues.

The first reason comes from the lawfulness general principle whereby Google has no lawful basis to process this personal data as the user refused consent, and no other legal basis is used. The second reason stems from the general principle of fairness, as users do not expect that, after refusing trackers and choosing the more privacy-friendly option, their data is still processed as if their consent choice did not matter.

Therefore, from Google’s perspective, GCM is privacy-friendly as no cookies are placed, thus no consent is required to be sought. However, a recent study revealed that personal data is still being processed without any permission or legal basis.

What next?

- On an individual level:

Many solutions have been developed for individuals to reduce the tracking they are subject to. From browser extensions to using devices that are more privacy-friendly and using ad blockers. One notable company tackling this issue is Duck Duck Go, which by default rejects trackers, allows for email protection, and overall reduces trackers when using their browser. Duck Duck Go is not the only company to allow this, many more, such as uBlock Origin and Ghostery, offer similar services.

Specifically, regarding fingerprint ID, researchers have developed ways to prevent device fingerprinting. In 2023, researchers proposed ShieldF, which is a Chromium add-on that reduces fingerprinting for mobile apps and browsers. Other measures include using an IP address that many people use, which is not ideal for home Wi-Fi. Using a combination of a browser extension and a VPN is also unsuitable for every individual, as this demands a substantial amount of effort and sometimes financial costs.

- On a systemic level:

CMPs and GCM are active tracking stakeholders in the tracking ecosystem, and their actions are subject to enforcement bodies. In this case, predominantly data protection authorities (DPA). One prominent DPA working on cookie enforcement is the Dutch DPA, the Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens (AP). In the early months of 2025, the AP has publicly stated that its focus for this upcoming year will be to check cookie compliance. They announced that they would be investigating 10,000 websites in the Netherlands. This has led to investigations into companies with unlawful cookie banners, concluding with warnings and sanctions.

However, these investigations require extensive time and effort. DPAs have already stated that they are overworked and do not have enough personnel or financial resources to cope with the increase in responsibility. Coupled with the fact that sanctioned companies set aside financial pots for these sanctions, or that non-EU businesses do not comply with DPA sanction decisions (the case of Clearview AI). Different ways to tackle non-compliance should be investigated.

For example, in light of the GDPR simplification package, whilst simplifying some measures, other liability measures could be introduced to ensure that enforcement is as vigorous as the legislation itself. The EU has not shied away from holding management boards liable for non-compliance. In a separate legislation on cybersecurity, NIS II Article 20(1) states that ‘management bodies of essential and important entities approve the cybersecurity risk-management measures (…) can be held liable for infringements (…)’. That article allows for board member liability for specific cybersecurity risk-management measures in Article 21. If similar measures cannot be introduced during this time, other moments of amendment can be consulted for this.

Conclusion

Cookies and device fingerprinting are two common ways in which tracking occurs. The potential larger societal and legal consequences of tracking demand that existing robust legislation is enforced to ensure that past politically related historical mistakes are not repeated.

Ultimately, there is no way to completely prevent fingerprinting and cookie-based tracking without significantly compromising the user’s browsing experience. For this reason, the burden of responsibility must shift toward CMPs. This shift should begin with the implementation of privacy-by-design and privacy-by-default principles in the development of their tools (preventing cookie placement prior to consent seeking).

Accountability should occur through tangible consequences, such as liability for board members in cases of negligence. By attributing responsibility to the companies which develop cookie banners and facilitate trackers, the source of the problem can be addressed and held accountable for their human rights violations.

Would you like to learn more about AI, tech and digital diplomacy? If so, ask our Diplo chatbot!