Digital Watch newsletter – Issue 45 – November and December 2019

Trends

Each month we analyse hundreds of unfolding developments to identify key trends in digital policy and the issues underlying them. These were the trends we observed in November and December.

1. Discussions on cyber issues continue at the UN

Across November and December UN member states engaged in discussions on issues surrounding cybercrime and information security. The Third Committee of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) passed a resolution on countering the use of ICT for criminal purposes. Proposed by Russia and 26 other countries, the resolution calls for the establishment of an open-ended ad hoc intergovernmental committee of experts from all regions, tasked with developing an international convention to combat cybercrime.

If the resolution is approved in the full UNGA, the resulting committee is expected to base its work on a draft convention proposed by Russia in 2017 on co-operation on combating cybercrime. This lists various crimes (including hacking), presents options for international co-operation, and proposes a contact and support centre for investigations.

In an open letter to the UNGA, 36 human rights groups warned that the draft convention could undermine the ability of the Internet to enable the exercise of human rights, as it could grant governments the power to block websites and services for political purposes. They invited member states to vote against the resolution in the GA.

There is another question as well: what would be the relationship of a new UN convention on cybercrime with the existing Budapest Convention, adopted in the Council of Europe and already ratified by more than 60 countries? What would it mean in practice if cybercrime became subject to two different international legal frameworks?

On information security issues, informal consultations were held by the working groups on developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security. The agendas of the Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) and the Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) were very similar: the cyber threat landscape; norms, rules and principles of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace; confidence building measures and capacity building.

The discussions were remarkably similar as well: phishing activities, autonomous technologies, and the terrorist use of propaganda were of interest to both groups. Each emphasised the importance of implementing the norms outlined in the previous UN GGE reports. On capacity building, both groups noted the need for sensitivity to regional and national contexts and that principles of national ownership, transparency, and sustainability must be respected. It was also clear that capacity building activities should be coordinated to avoid duplication of effort. However, what was left unanswered in both groups is how to apply international law in cyberspace. Read our reports from the OEWG consultations.

It is often reiterated that the work of the OEWG and GGE must be complementary. Yet there is a divergence of positions on what precisely should be their respective roles.[link] From the December informal consultations it seems that it should be possible to avoid the doubling of effort, but it is as yet unclear what happened behind the closed doors of the GGE’s first substantive meeting on 9–13 December.

2. Addressing misinformation during elections: banning political content and limiting microtargeting of political ads

Concerned that misinformation can influence electoral processes and undermine trust in democracy, governments have been putting increasing pressure on Internet companies to address the issue. In response, companies have started updating their policies on political advertising and the distribution of political content.

Twitter took a tough stance by instituting a ban on paid promotion of political content. This includes ‘content that references a candidate, political party, elected or appointed government official, election, referendum, ballot measure, legislation, regulation, directive, or judicial outcome’. CEO Jack Dorsey explained that, while followers implicitly accept political messages when they decide to follow an account, 'this decision should not be compromised by money' (paid ads).

The reactions to Twitter’s ban were mixed. Some applauded the move; others described it as ‘unnecessarily severe and simplistic’, as it may disadvantage challengers and political newcomers, and it makes Twitter the arbiter of what is and what is not political speech.

Google made a less drastic policy change: election ads can now use only general data (age, gender, and general location) in targeting audiences. The company also explained that it has never permitted granular microtargeting – a practice that allows advertisers to send messages to very small, specifically defined groups of people – of political ads on its platforms.

Prior to Twitter and Google’s moves, Facebook’s stance had been not to interfere with political advertisement, to protect free speech and avoid ambiguity about what constitutes political speech. But the company has faced increased pressure to take action and it is now looking into preventing microtargeting by political advertisers (for instance, by increasing the minimum number of people a political ad can target from the current limit of 100 to a few thousand).

These different positions adopted by the major Internet companies leave open several questions: Will Twitter’s ban on political advertising be more effective than Google and Facebook’s focus on how users are targeted by political ads? Should companies be entitled to determine what is political content? Is it enough to entrust companies with fighting misinformation, or should strict regulation be imposed? And, if regulation is the better approach, what should it look like?

3. Fighting deepfakes: technological tools and policy initiatives

Deepfakes use machine learning and neural network technology to falsify images and footage so as to make it appear that someone did or said something that they did not.

Deepfakes can be misused in different contexts: to discredit opponents in political campaigns, to cause personal reputational damage (for instance by making people appear in pornographic videos they were in fact not part of), and even to escalate situations that can lead to violent conflict. As the technology becomes increasingly sophisticated and accessible, tech companies and policymakers are trying to find solutions to the challenges it presents.

Technology offers some solutions: the same artificial intelligence (AI) tools that are used to produce deepfakes can also be used to detect them, and many companies and researchers are focusing on this area. Google and Facebook have built collections of fake videos and are making them available to researchers developing detection tools. Facebook has even launched a Deepfake Detection Challenge. Blockchain technology has also been suggested as a potential weapon in the fight against deepfakes: the authenticity of images and footage can be established through a blockchain application that compares the cryptographic hash code of certain files against that of the originals.

Technological solutions may not be sufficient to address the risks posed by deepfakes, especially given that detection methods tend to lag behind the fast-evolving creation methods. But tech-company policies and legislative solutions could complement technical tools. Twitter, for example, has announced that it is working on a policy to combat deepfakes and synthetic media on its platform. China has introduced new regulations that ban the distribution of deepfakes without proper disclosure that the content has been altered using AI. Failure to comply will be considered a criminal offence as of January 2020. Existing legislation may help as well: California has previously criminalised the publication of false audio, imagery, or video in political campaigns.

But what is certain is that, beyond developing technical tools and regulations, the fight against the abuse of deepfake technology will require that we promote awareness and critical thinking among end-users as well. An informed, tech-savvy and healthily sceptical public will, in the end, be central to ensuring that the Internet fulfils its potential as a force for positive change.

Digital policy developments

Digital policy is constantly evolving to keep pace with technological and geopolitical developments: the landscape is packed with new initiatives, evolving regulatory frameworks, and new legislation, court cases and judgments.

In the Digital Watch observatory – available at dig.watch – we decode, contextualise, and analyse these developments, offering a digestible yet authoritative update on the complex world of digital policy. The monthly barometer tracks and compares the issues to reveal new trends and to allow them to be understood relative to those of previous months. The following is a summarised version; read more about each one by following the blue icons, or by visiting the Updates section on the observatory.

Global IG architecture

same relevance

The 14th Internet Governance Forum (IGF) brought together more than 3000 participants to discuss current challenges around data governance; digital inclusion; and safety, security, stability, and resilience. Read more on pages 6–7.

The World Wide Web Foundation launched the Contract for the Web, formulating nine principles to protect the web as a force for good.

The Just Net Coalition launched a Digital Justice Manifesto that frames the discussion on data governance in the context of social justice, fairness, and public goods.

Sustainable development

same relevance

The International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU’s) report Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2019 confirmed continuing barriers to Internet access and use, especially in the least developed countries.

The 2019 Human Development Report called for policies and incentives to harness the power of digital technologies in the move towards sustainable development goals (SDGs).

Security

increasing relevance

The Third Committee of the UNGA passed a resolution on countering the use of ICT for criminal purposes.

BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) emphasised the central role the UN has to play in developing norms for responsible state behaviour in cyberspace. The UN GGE and OEWG held consultations with non-members on issues related to state behaviour in cyberspace. The GGE also held its first substantive session.

The Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace proposed a Cyberstability Framework and eight voluntary norms to better ensure the stability of cyberspace.

Facebook has decided to move ahead with introducing end-to-end encryption in its messaging apps.

Multiple cyber-attacks were revealed around the world, targeting government systems in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, the US state of Louisiana, and the city of New Orleans; a French hospital; Indian and UK nuclear power facilities; and the UK Labour Party.

E-commerce and Internet economy

increasing relevance

Transport for London decided not to grant Uber a new licence to operate in the city.

The Czech government proposed a 7% tax for global Internet giants. India expressed its dissatisfaction with the OECD Secretariat’s unified approach to taxing the digital economy. During the Canadian election, the Liberal party proposed a digital services tax.

World Trade Organization (WTO) member states agreed to keep the current practice of not imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions.

Digital rights

increasing relevance

Freedom House’s Freedom of the Net 2019 report shows a deterioration in the state of Internet freedom worldwide.

The European Commission intends to present a revised ePrivacy regulation proposal. The Indian Parliament is debating a new data protection bill.

Twitter announced updates to its privacy policy and launched a Privacy Centre.

Internet disruptions and shutdowns have been recorded in Iraq and Iran.

Twitter announced a ban on (almost) all political adverts, while Google is limiting adverts to those which use only general data to arget audiences. Facebook is considering limits on microtargeting in political advertising.

Jurisdiction and legal issues

same relevance

A bill proposed by the US Senate aims to make it illegal for US companies to store user data or encryption keys in China.

The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is reportedly expanding its antitrust scrutiny of Amazon’s cloud business.

Huawei filed a lawsuit with a US federal court claiming that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) acted improperly in barring rural carriers from using government subsidies to buy Huawei equipment.

Infrastructure

same relevance

RIPE Network Coordination Centre (RIPE NCC) exhausted its pool of IPv4 addresses.

The Internet Society announced the selling of the .org registry to private equity firm Ethos Capital, generating concerns over price hikes and potential human rights implications.

Microsoft plans to adopt the DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) security standard as a default in Windows 10.

The EU Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) published a report assessing the threat landscape for 5G networks.

Net neutrality

decreasing relevance

A coalition of technology companies and public-interest advocates asked a US Court of Appeals to revise a decision that upheld the FCC repeal of net neutrality rules.

New technologies (IoT, AI, etc.)

same relevance

Australia released a set of AI ethics principles. Russian President Vladimir Putin called for moral rules for human-AI interaction.

The Confederation of Laboratories for AI Research in Europe (CLAIRE), launched in The Hague, will focus on human-centred AI.

The Judicial Department of the city of Shaoxing used blockchain-secured evidence in a criminal decision.

The German Parliament adopted rules allowing banks to act as custodians for cryptocurrency funds. The French central bank is looking into the possibility of issuing digital currencies. The EU Council and the European Commission underlined that ‘no global “stablecoin” arrangement should begin operation in the EU until the legal, regulatory and oversight challenges and risks have been adequately identified and addressed’.

Developments

Each month Geneva hosts a diverse range of policy discussions in various forums. The following updates cover the main events in November and December. For event reports, visit the Past Events section on the GIP Digital Watch observatory.

Geneva Peace Week | 4–8 November 2019

This week-long conference highlighted both technology’s capacity to improve the quality of peace and its potential to disrupt peace and security. On the one hand, innovations in ICT have provided new opportunities for peace mediation. On the other, the cyber domain has become a new battlefield, prompting many countries to develop cyber military capacities both defensive and offensive. This new paradigm in international conflict and war raises urgent questions regarding the application of existing legal mechanisms such as international humanitarian law. Read our report from the conference.

CyberMediation Conference | 19 November 2019

This conference focused on the uses of digital technology in peace mediation and the opportunities and challenges the tech presents. Traditionally, peace mediation has taken place behind closed doors and involved a limited number of stakeholders. However, with the proliferation of ICTs and other digital technologies, there has been a shift towards more open and inclusive approaches. The conference highlighted the pressing need to plan how – and to what extent – digital technology should be integrated into mediation processes. Approaching this issue in an effective way will require the inclusion of all stakeholders.

The UN Forum on Business and Human Rights 2019 | 25–28 November 2019

Under the theme Time to act: Governments as catalysts for business respect for human rights, this conference provided perspectives from all stakeholders on ongoing and future efforts to protect human rights in business activities. Policy coherence among UN member states and benchmarking tools were emphasised as key elements in all such endeavours. Online slavery received in-depth discussion as a negative consequence of digitalisation and it was generally agreed that the issue needs to be addressed at local, national, and global levels.

The Future of Work Summit | 27 November 2019

In the context of the centenary of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the summit reflected on the pressing need to rethink collaboration processes and optimise digital tools for a more inclusive, productive, and sustainable future of work. Discussions scrutinised how technology is transforming the way people work and the skills they need to meet the resulting challenges. Debates also touched upon technology’s potential to help in reducing existing inequalities, including gender disparities in rates of employment and the pay gap between men and women.

Global Trade and Blockchain Forum | 2–3 December 2019

Organised by the WTO, the conference presented various sets of use cases of blockchain in international trade practices. It discussed how blockchain technology can be used in intellectual property (IP) intensive industries, and what the international community can do in terms of the regulation of blockchain and other digital technologies to avoid creating unnecessary barriers to trade. The gathering also served as an opportunity to discuss the role of international organisations in promoting and developing a regulatory and policy framework that allows us to harness the technology’s potential while mitigating its risks.

Berlin 2019: The dawn of a new IGF?

The Internet Governance Forum (IGF) convened for the 14th time between 25 and 29 November 2019 in Berlin. Under the theme One World. One Net. One Vision, the event brought together a record number of more than 3000 participants to discuss not only the most pressing Internet and digital policy issues of the day but also the future of the IGF itself.

Data governance, digital inclusion, safety and security

IGF 2019 revolved around three main themes: data governance; digital inclusion; and safety, security, stability, and resilience. This clear thematisation led to more focused and productive discussions, and several key takeaways emerged.

Debates over data governance focused on two competing needs: for the free flow of data across borders and for data localisation. Some argued for the importance of free data flows on the grounds that they play an essential role in enabling economic and societal development. Others emphasised political, security, and economic concerns to advocate for the prioritisation of data localisation policies. But possible routes out of this apparent binary also emerged. Constructive data governance solutions can be reached by distinguishing between types of data (e.g. personal, scientific, public) and the different safeguards and policies they require. This approach offers the possibility of governance frameworks that better reflect the differing needs of individuals, research organisations, businesses, and governments.

Discussions on digital inclusion began by acknowledging that a holistic approach is needed: inclusion starts with ensuring access to networks and devices but also requires much more. Community networks, public-private partnerships, and financial incentives are some of the measures that can contribute to building truly resilient infrastructures. Once they are in place, further policies and initiatives are needed to promote affordable access, education, financial inclusion, gender equality, and the availability of online content in local languages and scripts. Furthermore, meaningful digital inclusion will not have been achieved until users are able to use technology in ways that best address their needs (e.g. for information, education, economic opportunities, etc.)

The role of cyber norms in ensuring the security and stability of cyberspace dominated the discussions of cybersecurity. Voluntary norms can help to foster (more) responsible behaviour of states and other actors in cyberspace. But there are concerns about duplication of efforts across multiple forums, limited participation on the part of some actors, and the lack of institutional mechanisms to monitor and report on compliance. And while there was agreement that in theory international law applies to the behaviour of states in cyberspace, more work will be required in understanding and agreeing on what this means in practice.

Making cyberspace safe and stable is a joint responsibility. Responsible state behaviour is a clear necessity, but so are adequate laws, regulations and policies; the implementation of security standards within digital infrastructures, services, devices, etc; cybersecurity awareness and competence among end-users; and cross-stakeholder co-operation. Approaches to cyber-stability must balance measures to increase cybersecurity with the need to protect human rights, ethics, and trust.

From trustworthy AI to empowering SMEs

While these three themes were the focus of most sessions at IGF 2019, many others were touched on as well. GIP session reports and data analysis revealed other key areas of discussion and the takeaways they generated. Below are some of them; for a more comprehensive overview, check out our summary in the IGF 2019 Final Report.

-

We must foster the development and deployment of trustworthy AI systems that benefit all. Applying principles such as inclusivity, transparency, and explainability, and ensuring compliance with established human rights frameworks, are required if we are to ensure that AI does not widen digital divides and social inequalities.

-

More decisive action is needed to keep children safe online and empower them to exercise their digital rights. Possible measures include educational programmes, technical tools such as parental controls, and strengthened regulations to protect minors. Similarly, the online needs of women, gender minorities, and persons with disabilities deserve more attention from companies and regulators.

-

While many agree that cyberspace would benefit from more regulation in areas such as digital rights, cybersecurity, and illegal online content, how to regulate efficiently remains an open question. Regulations need to balance the rights and interests of different actors (e.g. protect users’ rights, while also encouraging innovation), respect democratic principles, and be based on inclusive and multistakeholder policy-making processes.

-

Maximised interoperability and harmonisation between national legal and regulatory frameworks are needed to prevent (more) fragmentation in cyberspace. This would also bring increased legal certainty for businesses and facilitate cross-border operations.

-

A thriving digital economy is one that empowers small and medium-sized enterprises to seize the opportunities offered by digital technologies. Elements of such an empowering environment include access to proper infrastructure (e.g. connectivity, cloud computing, e-payment services), access to financing, and tax policies that encourage investment.

-

In dealing with misinformation and harmful content online, existing self-regulatory measures (e.g. stringent content policies, codes of conduct, technical measures such as algorithms to identify and remove harmful content) are unlikely to be fit for purpose. Tech companies are under increased pressure to enhance their efforts and develop new solutions, but if these prove inadequate then governments are ready to step in with hard regulation.

The future of the IGF: implementing IGF Plus?

This year’s IGF represented a significant step forward. The more focused programme encouraged more in-depth and mature policy discussions. The record number of participants and the presence of stakeholders usually less well represented (including parliamentarians and actors from the global South) brought new energy and comprehensiveness to the debates. The presence of UN Secretary-General António Guterres and German Chancellor Angela Merkel demonstrated high-level support for the forum. Smooth organisation and remarkable facilities contributed to what was a highly successful gathering.

But will the success of IGF 2019 be enough to ensure the relevance of the IGF in the fast-evolving Internet governance and digital policy ecosystem? The answer is very likely not, especially considering that the forum did not achieve significant visibility outside its own circles. As a result, it is unlikely that the event’s outputs (e.g. messages, chair summary, best practice forums outcomes) will be broadly discussed in corporate boardrooms or government cabinets worldwide.

Implementing elements of the IGF Plus model proposed in the report of the UN Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation could be a solution. This model prompted considerable discussion in Berlin and received broad support as the most appropriate way forward, towards not only a robust and relevant IGF but also more generally a strengthened framework for international digital cooperation.

More discussions are needed on the implementation of the IGF Plus model. How to preserve the multistakeholder vibrancy and openness of annual meetings while producing more tangible outputs? Can the IGF issue policy recommendations without becoming a decision-making body? Where will the funds needed to support an IGF Plus come from? If these and other questions are addressed with responsibility, care, and urgency, we may see elements of a new IGF next year in Katowice.

The GIP Digital Watch observatory provided just-in-time reporting from IGF 2019. Visit the dedicated space to access reports from almost all sessions, Daily Briefs summarising the discussions, data analysis, video interviews, and a final IGF 2019 report. The just-in-time reporting initiative was carried out in collaboration with the IGF 2019 host country, the Internet Society, the Swiss authorities, and ICANN.

All I want for Christmas is … Data

With only a couple of days between us and 2020, the time has come to reflect on the year nearly past. What better way to do this than to look at the numbers.

In previous editions of this newsletter, we looked at the protection and violation of human rights online. Some of the issues we considered were the data protection investigations launched under the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and the current state of play regarding Internet shutdowns. This issue addresses another topic that may affect us all in one way or another: data breaches.

Data as a resource

Data is now regarded as the world’s most valuable resource. Humans are creatures that always seek to use metaphors from the tangible world to represent and understand new ideas and disciplines, and our approach to data is no different. Oil, bacon, gold are just some of the many analogies that have been used to evoke its value to society and the economy. Another is the image of the ‘data tsunami’, describing both the flood of information to which we are all exposed and the increasing availability of our own personal and sensitive data online. Yet another is nuclear waste, a bleak analogy that nevertheless fits perfectly: like nuclear waste, once data leaks ‘it is dangerous, long-lasting and ... there's no getting it back’.

Protecting data from breaches

In our increasingly digitalised society, personal data is collected, stored, and processed in a wide range of spheres. Governmental agencies store and process personal data in the contexts of healthcare, social security, tax collection, and educational systems, among others. Companies and organisations process the personal data of employees and contractors. And Internet companies collect and use personal data in ways of which we are sometimes not even aware.

Many jurisdictions around the world have legal and regulatory frameworks in place for the processing of personal data, obliging organisations to meet certain standards in the confidentiality and integrity of their systems. The GDPR is increasingly perceived as setting the standard for the protection of personal data and privacy in general, and it has inspired similar frameworks worldwide. These include the Californian Customer Privacy Act as well as Indian legislative efforts in these areas.

But what is the reality? How safe is our data from breaches and unauthorised disclosure?

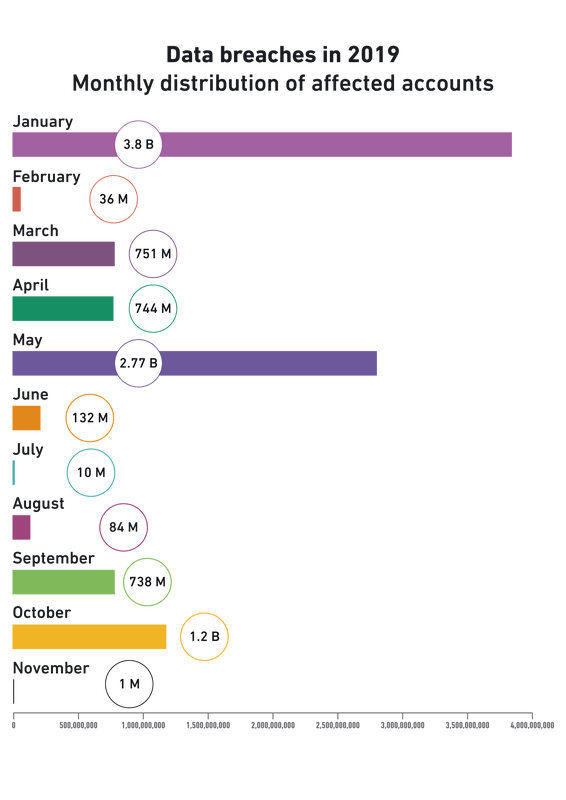

Data breaches in 2019

Even though it is hard to pinpoint the exact number of data breaches, given that they are not always reported, according to our analysis the cybersecurity landscape witnessed more than a hundred incidents over the course of 2019 (information was gathered from a variety of online sources including Have I Been Pwned and Selfkey). Our conclusion is that around 10 billion records have been publicly exposed, which represents almost a 100% increase over 2018. The research firm Risk Based Security corroborates this, calling 2019 the ‘worst year on record’ for data breaches.

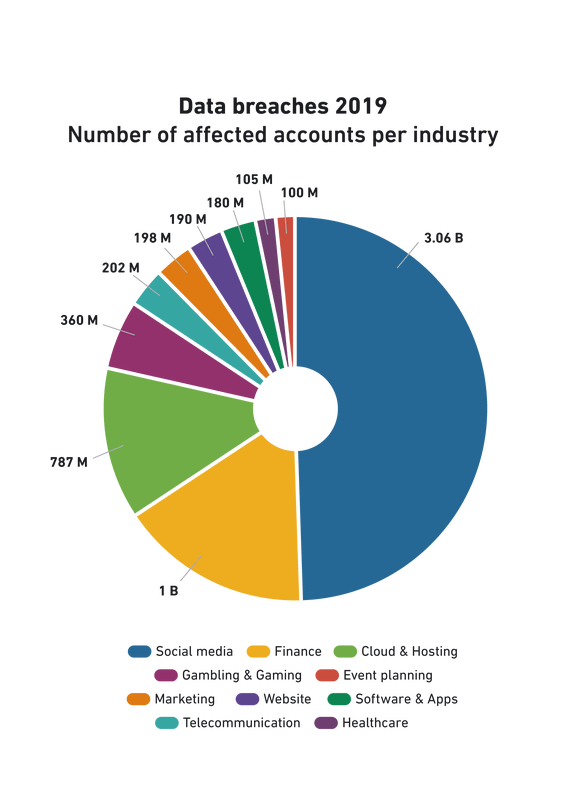

The largest data leakages came from unknown sources, amounting to a total of approximately 3 980 000 000 exposed records. The industry affected by the largest number of data incidents was healthcare, which is particularly worrisome. This, however, is not the only industry that leaves personal data vulnerable. The majority of exposures – roughly 3 billion – originated in social media data breaches.

The chart below depicts 26 industries affected by data breaches worldwide. The large majority of incidents occurred in the first half of the year, amounting to 69 incidents, in comparison to 32 in the second.

Data breaches have multiple causes. Sometimes the organisations processing the data do not have adequate technical measures in place, rendering their systems vulnerable to cyber-attack. Misconfigured or inappropriately secured databases, back-ups, and services are among the most frequent causes of incidents.

There is also the human factor, often considered the largest contributor to failures in cybersecurity overall. Data losses, misdelivery, and other types of human errors are among the most frequent occurrences of this sort. According to data gathered by risk consulting firm Kroll, 90% of all breaches reported to the UK Information Commissioner’s Office between 2017 and 2018 were caused by human error.

Top data breaches in 2019

-

US bank Capital One saw the data of more than 100 million US citizens and 6 million Canadian residents stolen by a hacker, including around 140 000 social security numbers and 80 000 bank account numbers.

-

In India, an unprotected database at the Department of Medical, Health and Family Welfare exposed the medical records of more than 12.5 million pregnant women.

-

In the USA, a data breach affecting mobile network operator T-Mobile exposed the data of over 1 million customers, including names, phone numbers, and addresses.

-

Another serious incident occurred when data analytics firm Ascension left more than 24 million financial documents (including names, addresses, social security numbers, and bank account numbers from financial institutions including HSBC Life Insurance, CitiFinancial and Wells Fargo) on an unprotected database for two weeks.

-

Bulgaria’s National Revenue Agency was the target of the country’s most serious data breach ever, one that compromised sensitive information (personally identifiable numbers, addresses, income data) of around 5 million citizens.

-

An attack against online graphic design tool Canva affected the accounts of around 139 million users, exposing information such as usernames, email addresses and passwords.

-

Marriott hotel group reported a hacking attack which affected the records of up to 383 million guests (including passport and credit card information).

-

A Toyota data breach exposed the personal information of 3.1 million customers, including name, date of birth, and employment information.

Is there a bullet-proof solution to the problem of data breaches? Nearly certainly not. As we witness more and more incidents year after year, the right question to ask is probably not whether but rather when an organisation will be affected by a breach. This is why organisations should focus their efforts not only on preventing breaches but on minimising their impact.

As for end-users, it’s high time we rethought our own data protection practices. And, wrapping up this year, that we perhaps add a new item to our wishlist – more privacy in 2020.

Upcoming events: Are you tuned in?

Learn more about the upcoming digital policy events around the world, and use DeadlineR to remind you about important dates and deadlines.

It’s the end of the year as we know it (and we’ll be fine)

As we looked back over 2019 an unexpected thought occurred: that the best way to understand the complex and rapidly evolving world of Internet and digital governance might be not graphs and statistics but an audio word cloud. Thus with great pleasure, we present to you Digital Watch’s revised version of REM’s It’s the end of the world as we know it, one of the most memorable hits of the decade when the Internet really took off. We suggest you sing it loudly in the shower, and add your own verses.

That’s great, it starts with a debate

Talk of change, it’s digital.

Connect me now, I’m lost in space

Include the lost, mind the cost.

Stop the hate, free the press

How can we clean up this mess?

Digital cooperation, awareness, education

Inclusion delusion disability reality.

Compact, convention, fake news, dissension

Relate co-operate exclusion confusion

Shut up shutdown who on earth is this clown?

Connection information cybercrime fragmentation.

ISOC ITU IPv6 who are you?

Copyright who’s left? Gender rights left behind.

Rule of law democracy find sustainability.

Trust trust it’s a must watch it now it’s going bust

Network design Google has it – no, it’s mine!

Cyberwar confrontation community opportunity.

It’s the end of the year as we know it,

Gotta keep on working, don’t you blow it.

It’s the end of the year as we know it,

And I feel blind.

(gotta find some time offline)

Norms responsibility confidence security

Emerging submerging content dialects

Convergence divergence encryption and children

Ethics, trust, AI, do it now it will fly.

Greta Thunberg, DotOrg, HumAInism, ‘holderism

Development #MeToo Who’s in charge? Wish we knew

Stability legality taxes economy

Literacy inequality infrastructure, now you see.

Privacy, dignity, data, data, can’t you see?

Algorithm, sing a song, bias has gotten it all wrong.

Technology, possibility, human computer, IoT.

We can do it, find the art. Common good, play the part.

IGF Plus Plus good idea, what’s the fuss?

Listen to us outside, IQ’whalo cannot hide.

It’s the end of the year as we know it,

Gotta keep on working, don’t you blow it.

It’s the end of the year as we know it,

We’re gonna be fine

(See you next year online)