July-August 2025 in retrospect

The digital and geopolitical landscape is shifting faster than ever—and understanding it is more important than ever. This month, our newsletter takes you behind the headlines and into the forces shaping technology, AI, and cybersecurity.

The levers of power: US chips vs China’s critical minerals – who really holds the keys to the future?

The global AI race: Rival powers, competing visions, and what it means for the future of AI.

Lessons from summer: From disillusionment to clarity: Ten insights for AI today.

Cyber frontlines: Digital intrusions are not just technical—they’re reshaping geopolitics.

UN OEWG wrap-up: A landmark step toward a permanent cybersecurity mechanism.

This summer in Geneva: Key events and takeaways shaping international digital governance.

Snapshot: The developments that made waves in July-August

DIGITAL GOVERNANCE

The co-facilitators for the WSIS+20 process issued the Zero Draft of the outcome document for the twenty-year review of the implementation of the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS+20).

At its 1 September summit in Tianjin, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) highlighted tech, AI, and digital governance, with a declaration stressing cyber sovereignty, inclusive AI, cybersecurity norms, and stronger digital cooperation.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

The UN General Assembly adopted a resolution setting out the framework for two new AI governance bodies—an Independent International Scientific Panel and a Global Dialogue—agreed under the 2024 Global Digital Compact (GDC).

The European Commission has released its finalised Code of Practice for general-purpose AI models, laying the groundwork for implementing the landmark AI Act. The new Code sets out transparency, copyright, and safety rules that developers must follow before deadlines. A new phase of the EU AI Act took effect on 2 August, requiring member states to appoint oversight authorities and enforce penalties.

Read more about this summer’s AI developments below.

TECHNOLOGIES

France and Germany announced a joint Economic Agenda, committing to joint efforts in AI, quantum, chips, cloud, and cybersecurity, while making digital sovereignty a central political and investment priority.

The USA, Japan, and South Korea held Trilateral Quantum Cooperation meetings to strengthen collaboration on securing emerging technologies.

The UK government unveiled its Digital and Technologies Sector Plan, aiming to grow the tech sector to £1 trillion, driven by AI, quantum computing, and cybersecurity.

Turkey’s government is preparing a long-awaited 5G frequency auction in October, with the Transport and Infrastructure Minister announcing that the first services should begin in 2026.

Two Chinese nationals were charged in the US for illegally exporting millions of dollars’ worth of advanced Nvidia AI chips to China over the past three years. Read more about this summer’s chip developments below.

INFRASTRUCTURE

Over 70 civil society and consumer groups have issued a statement warning that proposed interconnection fees in the EU’s upcoming Digital Networks Act could undermine net neutrality, raise costs, and stifle innovation.

In the US, several public-interest groups have opted not to appeal a January 2025 court ruling that struck down the FCC’s net neutrality rules, instead pursuing alternative federal and state strategies to protect open internet access.

A €40 million Baltic Sea digital infrastructure project, backed by €15 million from the EU’s Connecting Europe Facility (CEF2), will establish four subsea cables and several hundred kilometers of terrestrial fiber, creating a ~550 km long-haul route linking Sweden, Estonia, and Finland to expand Baltic Sea connectivity.

A new lawsuit filed by Cloud Innovation has intensified AFRINIC’s ongoing governance crisis, raising fears over the potential loss of African control of the continent’s internet infrastructure.

CYBERSECURITY

Australia’s eSafety commissioner report showed that tech giants made minimal progress in combating child sexual abuse online, with some failing to track reports or staff numbers, despite legally enforceable transparency notices requiring regular reporting under Australia’s Online Safety Act. https://dig.watch/updates/eu-sets-privacy-defaults-to-shield-minors

Germany’s highest court ruled that law enforcement may use secretly installed spyware to monitor phones and computers only in cases involving serious crimes.

A leaked memo reveals that the EU debate over mandatory private message scanning has intensified, with the European Parliament threatening to block the extension of voluntary rules unless the Council agrees to mandatory chat control.

Cybersecurity researchers have uncovered PromptLock, the first known AI-powered ransomware, a proof-of-concept capable of data theft and encryption that highlights how publicly available AI tools could escalate future cyberthreats.

INTERPOL has announced that a continent-wide law enforcement initiative targeting cybercrime and fraud networks led to more than 1,200 arrests between June and August 2025.

The Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) on the security of and in the use of ICTs wrapped up its final substantive session in July 2025 with the adoption of its long-awaited Final Report.

ECONOMIC

US President Donald Trump has officially signed the GENIUS Act into law, marking a historic step in establishing a legal framework for stablecoins in the US.

China is weighing plans to permit yuan-backed stablecoins in an effort to promote global use of its currency.

El Salvador’s National Bitcoin Office has split the country’s bitcoin reserves into multiple new addresses to bolster security, citing potential future risks such as quantum computing.

US President Donald Trump has threatened to impose retaliatory tariffs on countries implementing digital taxes or regulations affecting American technology companies.

China has proposed draft rules to ensure fair and transparent pricing on internet platforms selling goods and services, inviting public feedback following widespread complaints from merchants and consumers.

HUMAN RIGHTS

The UK’s new Online Safety Act has increased VPN use, as websites introduce stricter age restrictions to comply with the law.

Russian authorities have begun partially restricting calls on Telegram and WhatsApp, citing the need for crime prevention.

LEGAL

A Florida jury has ordered Tesla to pay $243 million in damages for a fatal 2019 Autopilot crash, ruling its driver-assistance software defective, which may significantly impact Tesla’s ambitions to expand its emerging robotaxi network in the USA.

The CJEU’s General Court has rejected a challenge to the EU–US Data Privacy Framework, allowing EU-to-US personal data transfers to continue without extra safeguards.

A United States federal judge has ruled against breaking up Google’s search business, instead ordering it to end exclusive deals, share data with rivals, and offer fair access to search and ad services after finding it illegally maintained its monopoly. However, the company has been hit with a 3.5 billion fine in the EU for abusing its dominance in digital advertising by giving unfair preference to its own ad exchange, AdX, in violation of EU antitrust rules.

France’s data protection authority CNIL has fined Google €350 million and SHEIN €150 million for unlawful cookie practices and consent violations.

Anthropic has agreed to a record $1.5 billion settlement with authors over claims it used their work without permission to train its AI models, pending court approval.

SOCIOCULTURAL

Brazil’s Attorney General (AGU) has formally requested Meta to remove AI-powered chatbots that simulate childlike profiles and engage in sexually explicit dialogue, citing concerns that they ‘promote the eroticisation of children.’

Australia announced plans to introduce legislation requiring tech companies to block AI tools that generate nude images or facilitate online stalking.

In Nepal, mass protests erupted over a 24-hour social media ban of 26 platforms and government corruption, resulting in 19 deaths.

US President Trump called security and privacy concerns around TikTok highly overrated and said he’ll keep extending the deadline for its parent company, ByteDance, to sell its controlling stake in TikTok or face a nationwide ban.

DEVELOPMENT

The EU will require all platforms to verify users’ ages using the EU Digital Identity Wallet by 2026, with initial pilots in five countries and fines of up to €18 million or 10% of global turnover for non-compliance.

France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands signed the founding papers for a new European Digital Infrastructure Consortium for Digital Commons, which will focus on publicly developed and publicly usable digital programmes.

The UN Secretary-General’s July report elaborates on a voluntary Global Fund for AI, targeting $1–3 billion to support countries’ AI readiness through foundational resources, national strategies, and cooperation.

Achieving universal internet connectivity by 2030 could cost up to $2.8 trillion, an ITU–Saudi CST report warns, urging global cooperation and investment to bridge widening digital divides and connect the one-third of humanity still offline.

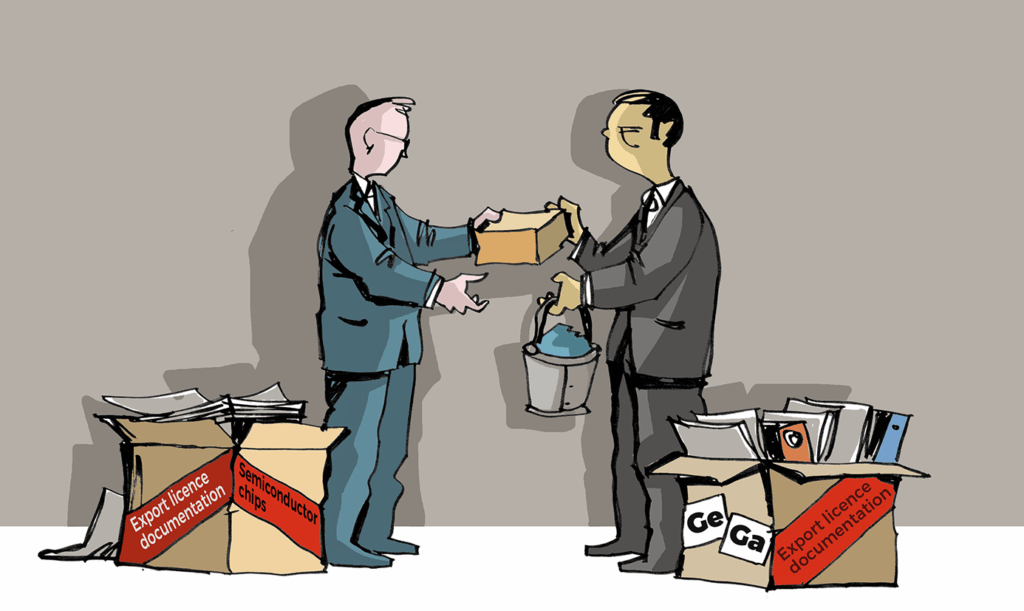

The levers of power: US chips vs China’s critical minerals

For years, semiconductors have been at the heart of the US–China technology rivalry, shaping trade negotiations, export controls, and national security debates. Nvidia’s latest struggle to sell its H20 chip in China is the latest chapter in a long-running standoff, highlighting how advanced technology, critical minerals, and industrial policy have become intertwined in global power politics.

The H20 chip, launched last year to help Nvidia maintain access to the Chinese market — which made up 13% of its sales in 2024 — was itself a product of geopolitics. However, in April, Washington told the company it needed a special license to export the H20 chip to China, halting shipments. The chip was believed to have powered DeepSeek, one of China’s most advanced AI models, raising US concerns about national security.

Nvidia reapplied for licenses in July and received assurances that they would be approved. Sales eventually resumed, but only after months of back-and-forth that reflected Washington’s shifting stance: In July, export controls were paused to bolster US-China trade negotiations. In August, the administration oscillated between threatening to block advanced Nvidia sales to China and signalling possible approval for modified versions.

In September, sales restarted, albeit under unusual circumstances: Going forward, Nvidia will give the US government 15% of its chip revenue from China, a deal that’s largely been described as unprecedented. AMD will do the same.

The bigger picture is: China’s controls on rare earth exports became a major focus in the trade talks between Beijing and Washington this summer. Why does it matter? Because chip manufacturing relies heavily on critical minerals like germanium and gallium. The USA is heavily reliant on imports for both of these critical minerals, especially from China, given its dominant role as a major producer and supplier of both products. According to a US Mineral Commodity Summary, no domestic primary (low-purity, unrefined) gallium has been recovered since 1987, and there are no government stockpiles of the mineral. The USA does produce germanium, but as a byproduct recovery from zinc ores, not a primary product, a process that is costly. A strategic stockpile of 5 tonnes of germanium does exist, but it is a paltry number compared to China’s reported 199 tonnes of annual germanium production. (Sidenote: The numbers are, unfortunately, from 2023, but they paint a clear enough picture.)

China, meanwhile, relies on NVIDIA’s chips to stay competitive in the global AI race. Domestic alternatives are still behind in performance, efficiency, and reliability, so using NVIDIA hardware allows China to deploy cutting-edge AI solutions immediately while its homegrown industry continues to scale up.

The USA openly linked chip concessions to rare earths discussions: In exchange for increasing shipments of rare earth minerals from China, the US agreed to lift export curbs on microchip designing software, ethane and jet engines.

The interplay between chip access and mineral supply illustrates a complex trade-off: each side leverages what it has — the USA its semiconductor know-how, China its dominance in rare earth minerals.

Both countries have already tried with export controls, with mixed results. Reports surfaced that more than $1 billion worth of Nvidia chips had already reached China through alternative channels. This prompted the USA to consider embedding trackers into AI chip shipments to monitor possible diversions.

Despite China’s export restrictions, germanium and gallium continue to reach the USA via indirect trade routes, likely through re-exports from countries where China permits their export.

This data underscored doubts about whether export controls could truly contain the spread of advanced technology and prompted each of the players to make moves to position themselves better and reduce their reliance on each other.

The USA: Leveraging the CHIPS Act

The USA reportedly is weighing the diversion of $2 billion 2022 CHIPS and Science Act in funding toward critical minerals.

Washington has also considered taking equity stakes in US chipmakers in exchange for cash grants authorised by the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act, aimed at supporting domestic semiconductor manufacturing and research. So far, the administration has signalled it will convert $8.87 billion in CHIPS Act grant money that had been awarded to Intel into 10% equity in the company. While Intel confirmed it had received a grant, officials insisted negotiations were still ongoing, underscoring the lack of clarity. The White House has denied plans to pursue similar stakes in firms like TSMC or Micron, but officials hinted that other companies could still be subject to action.

Critics argue that government ownership risks undermining global competitiveness, and some analysts question whether recent interventions — including Trump’s claim to have ‘saved Intel’ — are more political theatre than industrial strategy.

Adding to the confusion, the US Commerce Department voided a $7.4 billion research grant signed under the Biden administration, further muddying the picture of America’s long-term semiconductor policy.

Tariffs are also a weapon the USA will be wielding: President Trump has said that the USA will impose a tariff of about 100% on imports of semiconductors, though companies that produce chips domestically—or have committed to do so—will be exempt. China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) and Huawei are likely to be impacted.

China: Managing Nvidia concerns while boosting local production

Beijing, meanwhile, has tried to play both offence and defence.

Reports say that China-linked hacker group APT41 sent a malware-laden email posing as Rep. John Moolenaar, embedding malware to target U.S. trade groups, law firms, and agencies in a bid to gain insights into recommendations to the White House for the contentious trade talks. The Chinese embassy in Washington refuted the claims.

Authorities demanded Nvidia explain alleged flaws in the H20 chips, while state media went further, warning that the chips were unsafe for domestic use. Nvidia denied the accusations, stressing that its products contained no backdoors.

The country is accelerating efforts to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers: it aims to triple domestic AI chip production, while tech giants such as Alibaba are unveiling homegrown alternatives.

Other Asian players are also navigating this fractured landscape.

In July, Malaysia’s trade ministry announced that the export, transhipment, and transit of US-origin high-performance AI chips will now require a trade permit, effective immediately.

South Korea secured exemptions for Samsung and SK Hynix from 100% tariffs on semiconductor exports to the USA, as both companies have invested in the USA since 2022. TSMC, which is based in Taiwan (which the USA considers a part of China), also invested significantly in the USA. If they come to pass, these tariffs will be devastating for the Philippines, as about 70% of its total exports come from the semiconductor industry. Specifically, 15% of Philippine semiconductor exports—about $6 billion—are destined for the USA.

However, Washington revoked fast-track export status for Samsung, SK Hynix, TSMC, and Intel, making it harder to ship American chipmaking equipment and technology to their manufacturing plants in China. From 31 December, shipments of American-origin chipmaking tools to Chinese facilities will require US export licenses. However, the US Commerce Department is now weighing annual approvals for exports of chipmaking supplies to Samsung’s and SK Hynix’s China-based plants.

Who has the edge?

The US leads in chip design and advanced production, but its edge relies on access to critical minerals controlled by China. Beijing dominates the mineral supply but remains dependent on foreign high-end chips until domestic AI production scales up. In short, the US advantage is technologically superior but fragile, while China’s leverage is immediate but limited. The USA must find different sources of germanium and gallium, or figure out substitutions (such as inulin and silicone), while China must boost domestic chipmakers. How quickly each side addresses its weaknesses will shape the future of global tech dominance. And it won’t happen overnight.

The global AI race: Rival powers, competing visions

The global race for AI dominance is intensifying, as countries continue to roll out ambitious strategies to shape the future of AI. In the USA, the White House has launched a sweeping initiative through its publication Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan, a comprehensive strategy aiming to cement US leadership in AI by promoting open-source innovation and streamlining regulatory frameworks. This ‘open-source gambit’ is a marked shift in US digital policy, seeking to democratise AI development to stay ahead of global competitors, particularly China.

This aggressive policy direction has found backing from major tech companies, which have endorsed President Trump’s AI deregulation plans despite growing public concern over societal risks. Notably, the plan emphasises ‘anti-woke’ AI frameworks in government contracts, sparking debates about the ideological neutrality and ethical implications of AI technologies in public administration.

Across Europe, nations are accelerating their AI initiatives. Germany is planning an AI offensive to catch up on critical technologies, while the UK is aiming for a £1 trillion tech sector with AI and quantum technology growth.

Asian nations are increasingly positioning AI at the centre of their economic and technological strategies. South Korea is prioritising AI-driven growth through major infrastructure and budget investments. The initiative includes the creation of an ‘AI expressway’, starting with the Ulsan AI data centre, underpinned by bold tax incentives and regulatory reforms to attract private sector investment. Complementing this is a proposed investment of 100 trillion KRW (71 billion USD) to accelerate AI innovation, next-generation semiconductors, and the development of AI infrastructure and innovation zones.

Meanwhile, other countries in the region are pursuing similarly ambitious initiatives: Indonesia is creating a ‘sovereign AI fund’ and strengthening digital sovereignty and AI talent; Singapore has launched a $27 billion initiative to boost AI readiness and protect jobs; Kazakhstan is establishing new digital headquarters to embed AI across public services, and North Korea is dispatching AI researchers, interns and students to countries such as Russia in an effort to strengthen its domestic tech sector.

Across Africa, governments and partners are turning to AI as a catalyst for growth and governance reform, with national strategies and international investments converging to shape the continent’s digital future. Zimbabwe plans to launch a national AI policy to accelerate the adoption of the technology. Nigeria is preparing a national framework to guide responsible use of AI in governance, healthcare, education and agriculture. Japan has pledged $5.5 billion in loans and announced an ambitious AI training programme to deepen economic ties with Africa.

Latin America, by contrast, continues to struggle to join the global AI race. According to a July 2025 study by the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Latin America is lagging behind most advanced economies in terms of AI spending. The region’s spending reached US$2.6 billion in 2023, representing only 1.56% of global AI spending, while the region’s economy represents nearly 6.3% of global GDP. The study urges Latin America to accelerate AI adoption, especially among SMEs, by boosting skilled labour through education and training, promoting sector-specific use cases, and establishing technology centres. Without these measures, the region risks underusing AI’s potential despite its significant economic weight.

Amidst this competitive landscape, there are also moves toward international cooperation. China’s Global AI Governance Action Plan, published just days after America’s AI Action Plan, calls for an inclusive AI governance model with multistakeholder participation. China proposed the establishment of an international AI cooperation organisation, hoping to ‘assist countries in the Global South to strengthen their capacity-building, nurture an AI innovation ecosystem, ensure that developing countries benefit equally from waves of AI, and promote the implementation of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.’ This idea recently received support from Kazakhstan.

It is currently unclear how this newly international AI cooperation organisation would interplay with the UN Independent International Scientific Panel on AI and a Global Dialogue on AI Governance, which China has expressed support for, and whose operational details were set out at the end of the summer. The creation of these mechanisms was formally agreed by UN member states in September 2024, as part of the GDC. In August, the UNGA resolution A/RES/79/325 set out their terms of reference and modalities.

The 40-member Scientific Panel has the main task of ‘issuing evidence-based scientific assessments synthesising and analysing existing research related to the opportunities, risks and impacts of AI’, in the form of one annual ‘policy-relevant but non-prescriptive summary report’ to be presented to the Global Dialogue. The Panel will also ‘provide updates on its work up to twice a year to hear views through an interactive dialogue of the plenary of the General Assembly with the Co-Chairs of the Panel’.

The Global Dialogue on AI Governance, to involve governments and all relevant stakeholders, will function as a platform ‘to discuss international cooperation, share best practices and lessons learned, and to facilitate open, transparent and inclusive discussions on AI governance with a view to enabling AI to contribute to the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals and to closing the digital divides between and within countries’.

Another GDC commitment was a Global Fund for AI to scale up AI capacity development for sustainable development. The UN Secretary-General’s report on Innovative Voluntary Financing Options for AI Capacity Building (A/79/966), published this July, proposes a Global Fund for AI with an initial target of US $1–3 billion. It would help countries advance in AI readiness, focusing on foundations (compute, data, skills) and enablers (national strategies, cooperation). Funding would rely on voluntary government, philanthropic, private sector, and development bank contributions, with governance through a steering committee, technical panels, and multistakeholder input. Options for capitalisation include a small levy on tech transactions, digital asset contributions, and co-financing with banks, alongside tools such as AI bonds, conditional debt forgiveness, and blended financing. A coordination platform is also proposed to align funders, improve strategic coordination, and standardise monitoring. The report will be considered by the UNGA.

Whether the coming years bring fragmentation into rival technological spheres or a fragile framework for cooperation will depend on how states reconcile national ambitions with global responsibilities. The outcome of this delicate balance may determine not only who leads in AI, but how humanity as a whole lives with it.

From summer disillusionment to autumn clarity: Ten lessons for AI

As students return to classrooms and diplomats to negotiation tables, the question looms: where is AI really heading?

This summer marked a turning point. The dominant AI narrative, bigger is better, collapsed under its own weight. That story ended this August, with the much-hyped launch of GPT-5.0. Bigger models are not necessarily smarter models, and exponential progress cannot be sustained by brute force alone.

This autumn, then, can be a season of clarity. In the following analysis, we outline ten lessons from the summer of AI disillusionment, developments that will shape the next phase of the AI story.

1. Hardware: More is not necessarily better; small AI matters. Nvidia’s rise epitomised the belief that more compute ensures AI progress, but GPT-5 and new studies show diminishing returns. Core model flaws persist, prompting a shift from mega-systems toward diversified, smaller-scale hardware tailored to specific applications.

2. Software: The open-source gambit. Open-source AI surged in 2025, led by China’s DeepSeek and mirrored in the US strategy, challenging the dominance of closed labs. With strong performance at lower cost, open models spread rapidly, reframing debates on safety and shifting power dynamics. Open code became both a tool for innovation and a form of geopolitical soft power.

3. Data: Hitting the limit and turning to knowledge

AI is running out of high-quality training data, pushing a shift from raw text to structured human knowledge. Companies now court experts, adopt retrieval-augmented systems, and build knowledge graphs to ground outputs. This raises governance questions over ownership and fairness, as the risk grows that collective knowledge could be enclosed by a few corporations.

4. Economy: Between commodity and bubble

AI is both a cheap commodity and a speculative bubble. Open models and efficient tools democratise access, while massive investment inflates valuations and risks a crash. The challenge is distinguishing hype from real value: supporting sustainable applications while avoiding the fallout of an overheated market.

5. Risks: From existential to existing

The debate has shifted from distant existential threats to tangible present-day harms—bias, job loss, misinformation, and accountability. Overhyped AGI timelines have lost credibility, while regulators and civil society increasingly push to address AI as a product subject to current laws. Tackling today’s risks builds trust and stability for AI’s future.

6. Education: The front line of disruption

AI has upended traditional teaching by automating essay writing and assessments, creating both crisis and opportunity. Schools must shift from banning AI to rethinking pedagogy—focusing on critical thinking, creativity, and human judgment—while using AI to personalise learning and offload routine tasks. Education reform will determine whether students become AI-empowered or AI-dependent.

7. Philosophy: From ethics towards epistemology

Debates are moving beyond checklists of “AI ethics” toward deeper questions of knowledge and truth. As AI-generated content shapes cognition, concerns focus on how we know, who defines truth, and what reliance on algorithms does to human agency. This epistemological turn reframes AI not just as a tool but as a force reshaping understanding itself.

8. Politics and regulation: Techno-geopolitical realism

The USA, China, and EU now treat AI as strategic infrastructure, tying it to economic security and global power. Washington prioritises dominance and supply chain control; Beijing accelerates national integration and champions open-source abroad; Brussels pushes sovereignty through investment and regulation. Lofty AGI fears have given way to pragmatic competition, with cooperation at risk but realism rising.

9. Diplomacy: The UN moves slowly but surely

The UN has emerged as a steady player in AI governance, adopting resolutions that stress capacity-building, funding, and inclusive cooperation. Proposals include a Global Fund for AI, an international scientific panel, and a Global Dialogue. Though success depends on political will and financing, the UN is carving a role as a legitimate, development-focused convener.

10. Narrative collapse: From hype to realism

The AI hype cycle is deflating, exposing overblown promises and forcing a reset. Long-term doom predictions and inflated valuations are giving way to sober focus on practical applications, human knowledge, and local empowerment. This narrative shift—if matched with transparency and tech literacy—could mark the start of a more grounded, human-centred AI era.

This summary is adapted from Dr Jovan Kurbalija’s article ‘From summer disillusionment to autumn clarity: Ten lessons for AI.’ Read the full article.

Cyber frontlines: How digital intrusions are redrawing geopolitics

This summer has seen a surge of cyberattacks linked to state-backed groups, underscoring how digital intrusions have become a central feature of geopolitical rivalry.

Microsoft has again become the focal point of high-stakes cyber operations. A flaw in its SharePoint software has triggered a wave of attacks that spread rapidly from targeted espionage into broader exploitation. Google and Microsoft confirmed that Chinese-linked groups were among the first movers, but soon both cybercriminals and other state-sponsored actors joined in. More than 400 organisations have reportedly been compromised, making the incident one of the most far-reaching Microsoft-linked breaches since the Exchange server attacks in 2021. The sheer scale of the breach—the compromise of millions of personal data records—demonstrated the blurring of lines between espionage, mass surveillance, and strategic influence operations.

A new joint cybersecurity advisory (CSA) was released on 27 August by over a dozen international law enforcement organisations, exploring the inner workings of Chinese APT threats.

The episode has further sharpened tensions between Washington and Beijing. While the USA accused China of orchestrating intrusions through Salt Typhoon group—an operation that siphoned off data from millions of Americans—Beijing countered with claims that the USA itself had weaponised a Microsoft server vulnerability for offensive operations. In parallel, Microsoft announced restrictions on Chinese access to its cyber early warning system, signalling a deliberate shift in how it manages security cooperation with China.

In Asia, Chinese-linked groups infiltrated telecom networks across Southeast Asia and also targeted Singapore’s critical infrastructure, prompting a government investigation.

Russian-linked operations remain among the most disruptive, blending espionage, sabotage, and hybrid tactics. In the USA, federal courts confirmed that their systems were targeted by a cyberattack, with reports suggesting Moscow was responsible. The FBI separately warned that Russian groups continue to probe critical infrastructure by targeting networking devices associated with critical infrastructure IT systems.

In Europe, Russia is suspected of orchestrating sabotage and hybrid pressure campaigns. Norway’s intelligence chief attributed the sabotage of a dam in April to Russian hackers, while Brussels reported GPS jamming that disrupted European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s flight, also linked to Moscow. These incidents suggest that the increasing willingness of threat actors to deploy cyber and electronic warfare not only against military targets but also against civilian infrastructure and political figures. Italy faced its own test when suspected Indian state-backed hackers targeted defence firms, suggesting that middle powers are increasingly entering the state-backed cyber arena.

Nowhere is the fusion of cyber and kinetic conflict clearer than in Ukraine. By meticulously gathering and analysing digital data from the conflict within its borders, Ukraine has provided invaluable insights to its allies. This trove of information demonstrates how digital forensics can not only aid in defence but also strengthen international partnerships and understanding in a complex world.

In a fraught environment such as this, there is a continuous effort to manage risk, protect systems, and navigate the intricate diplomatic realities of the digital age. The irony is that as these attacks unfolded, so did the negotiations at the UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on cybersecurity, which culminated in the successful adoption of the group’s Final report. The OEWG plays a central role in making cyber rules, providing a forum where states negotiate norms, principles, and rules of responsible behaviour in cyberspace. Yet what good are rules if not implemented? The OEWG has historically struggled to translate non-binding norms into practice: one such rule from 2015 prohibits allowing criminal activity to operate from national territory, but the cyberattacks this summer—and, let’s be frank, since 2015—prove otherwise. Yet, the Global Mechanism, which was agreed upon in the Final report, could bring a change. States will have the opportunity to draft and ultimately adopt action-oriented recommendations—let’s see how they will use it in the future.

UN OEWG concludes, paving way for permanent cybersecurity mechanism

The OEWG on ICT security has adopted its Final Report after intense negotiations on responsible state behaviour in cyberspace. As always, compromises among diverse national interests – especially the major powers – mean a watered-down text. While no revolutionary progress has been made, there’s still plenty to highlight.

States recognised the international security risks posed by ransomware, cybercrime, AI, quantum tech, and cryptocurrencies. The document supports concepts like security-by-design and quantum cryptography, but doesn’t contain concrete measures. Commercial cyber intrusion tools (spyware) were flagged as threats to peace, though proposals for oversight were dropped. International law remains the only limit on tech use, mainly in conflict contexts. Critical infrastructure (CI), including fibre networks and satellites, was a focus, with cyberattacks on CI recognised as threats.

The central debate on norms focused on whether the final report should prioritise implementing existing voluntary norms or developing new ones. Western and like-minded states emphasised implementation and called for deferring decisions on new norms to the future permanent mechanism, while several developing countries supported this focus but highlighted capacity constraints. In contrast, another group of countries argued for continued work on new norms. Some delegations, such as sought a middle ground by supporting implementation while leaving space for future norm development. At the same time, the proposed Voluntary Checklist of Practical Actions received broad support. As a result, the Final Report softened language on additional norms, while the checklist was retained for continued discussion rather than adoption.

The states agreed to continue discussions on how international law applies to the states’ use of ICT in the future Global Mechanism, confirming that international law and particularly the UN Charter apply in cyberspace. The states also saw great value in exchanging national positions on the applicability of international law and called for increased capacity building efforts in this area to allow for meaningful participation of all states.

The agreement to establish a dedicated thematic group on capacity building stands out as a meaningful step, providing formal recognition of CB as a core pillar. Yet, substantive elements, particularly related to funding, were left unresolved. The UN-run Global ICT Security Cooperation and Capacity-Building Portal (GSCCP) will proceed through a modular, step-by-step development model, and roundtables will continue to promote coordination and information exchange. However, proposals for a UN Voluntary Fund and a fellowship program were deferred.

Prioritising the implementation of existing CBMs rather than adopting new ones crystallised during this last round of negotiation, despite some states’ push for additional commitments such as equitable ICT market access and standardised templates. Proposals lacking broad support—like Iran’s ICT market access CBM, the Secretariat’s template, and the inclusion of Norm J on vulnerability disclosure—were ultimately excluded or deferred for future consideration.

States agreed on what the future Global mechanism will look like and how non-governmental stakeholders will participate in the mechanism. The Global mechanism will hold substantive plenary sessions once a year during each biennial cycle, work in two dedicated thematic groups (one on specific challenges, one on capacity building) that will allow for more in-depth discussions to build on the plenary’s work, and hold a review conference every five years. Relevant non-governmental organisations with ECOSOC status can be accredited to participate in the substantive plenary sessions and review conferences of the Global Mechanism, while other stakeholders would have to undergo an accreditation on a non-objection basis.

This summer in Geneva: Developments, events and takeaways

WSIS+20 High-Level Event 2025

This summer, Geneva became the stage for a most significant global digital gathering. From 7 to 11 July 2025, the city hosted the WSIS+20 High-Level Event, held alongside the AI for Good Global Summit.

The week-long deliberations were framed as part of preparations for the UN General Assembly’s WSIS+20 Review, scheduled for 16–17 December 2025. That review will reaffirm international commitment to the WSIS process and set strategic direction for the next two decades of digital cooperation.

The Chair’s Summary, issued by South Africa’s Minister of Communications Solly Malatsi, underscored WSIS’s role as a cornerstone of global digital cooperation. Over the past twenty years, the WSIS architecture — anchored in the Geneva Plan of Action and the Tunis Agenda — has expanded connectivity, empowered users, and guided national and international strategies to bridge digital divides. Today, more than 5.5 billion people (68% of the world’s population) are online, up from fewer than one billion in 2005. Yet 2.6 billion people remain unconnected, concentrated in developing countries, least developed countries, and marginalised communities, making universal connectivity the most urgent unfinished task.

Some discussions in Geneva revolved around how to adapt the implementation of WSIS Action Lines to new realities: the rise of AI, quantum, and space technologies; persistent digital divides; and the implementation of the GDC. Participants largely agreed that existing mechanisms — the WSIS Forum, the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), and initiatives such as AI for Good — are indispensable, and ideally positioned to implement the GDC and translate its principles into measurable action.

Several themes stood out. First, the need to ensure that digital governance keeps pace with unpredictable technological progress, while safeguarding human rights, cultural and linguistic diversity, and local realities. Second, the importance of youth engagement: more than 280 young people participated in a dedicated Youth Track, proposing co-leadership roles, grassroots funds, and a permanent WSIS Youth Programme. Third, recognition that inclusion must go beyond connectivity to encompass affordability, digital skills, and rights-based participation.

Participants also emphasised that the WSIS process must continue to link digital innovation with sustainability goals, integrating green technology and climate-smart solutions. Ethical and rights-based approaches to AI and other emerging technologies were highlighted as essential, alongside stronger international cooperation to address cybersecurity threats, disinformation, and online harms.

The Chair’s Summary concluded with a clear message: WSIS will remain the central platform for advancing digital cooperation beyond 2025, ensuring that the gains of the past two decades are consolidated while adapting to new realities. True inclusion, it stressed, is not only about being present but about being heard — there is a need to engage those still excluded, reflect diverse local and global experiences, and continue advancing WSIS’s vision of an equitable, people-centred information society over the next 20 years.

Our session reports and AI insights from both events can be found on the dedicated WSIS+20 High-Level Event 2025 and AI for Good Global Summit 2025 web pages on the Digital Watch Observatory.

Zero Draft of WSIS+20 outcome document

In the lead-up to the UN General Assembly’s high-level meeting dedicated to the WSIS+20 Review, scheduled for 16–17 December 2025, negotiations and consultations are focused on concrete text for what will become a WSIS+20 outcome document. This concrete text – called the zero draft – was released on 30 August.

Digital divides and inclusion take centre stage in the zero draft. While connectivity has expanded – 95% of the global population is now within reach of broadband, and internet use has grown from 15% in 2005 to 67% in 2025 – significant gaps remain. Disparities persist across countries, urban and rural areas, genders, persons with disabilities, older populations, and minority language speakers. The draft calls for affordable entry-level broadband, local multilingual content, digital literacy, and mechanisms to connect the unconnected, ensuring equitable access.

The digital economy continues to transform trade, finance, and industry, creating opportunities for small and women-led businesses but also risks deepening inequalities through concentrated technological power and automation. Against this backdrop, the draft outlines a commitment to supporting the development of digital financial services, and a call for stakeholders to foster ‘open, fair, inclusive and non-discriminatory digital environments.

Environmental sustainability is a key consideration, as ICTs facilitate monitoring of climate change and resource management, yet their growth contributes to energy demand, emissions, and electronic waste. Standing out in the draft is a call for the development of global reporting standards on environmental impacts, and of global standards for sustainable product design, and circular economy practices to align digital innovation with environmental goals.

The Zero Draft reaffirms human rights, confidence and security, and multistakeholder internet governance as central pillars of the digital ecosystem. Human rights are positioned as the foundation of digital cooperation, with commitments to protect freedom of expression, privacy, access to information, and the rights of women, children, and other vulnerable groups. Strengthening confidence and security in the use of technology is seen as essential for innovation and sustainable development, with emphasis on protecting users from threats such as online abuse and violence, hate speech, and misinformation, while ensuring safeguards for privacy and freedom of expression.

The draft outlines a series of key (desirable) attributes for the internet – open, free, global, interoperable, reliable, secure, stable – and highlights the need for more inclusive internet governance discussions, across stakeholder groups (governments, the private sector, civil society, academia, and technical communities) and across developed and developing countries alike.

To advance capacity building in relation to AI, the draft proposes a UN AI research programme and AI capacity building fellowship, both with a focus on developing countries. In parallel, the draft welcomes ongoing initiatives such as the Independent International Scientific Panel on AI and the Global Dialogue on AI Governance.

Recognising the critical importance of global cooperation in internet governance, the draft designates the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) as a permanent UN body and calls for enhanced secretariat support, enhanced working methods, and reporting on outcomes to UN entities and processes (which are then called to duly take these outputs into account in their work). The long-discussed issue of IGF financial sustainability is addressed in the form of a request for the UN Secretary-General to make proposals on future funding.

Finally, the draft looks at the interplay between WSIS, the Global Digital Compact and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and outlines several mechanisms for better connecting them and avoiding duplication and overlaps. These include a joint WSIS-GDC implementation roadmap, the inclusion of GDC review and follow-up into existing annual WSIS mechanisms (at the level of the Commission on Science and Technology for Development and the Economic and Social Council), and reviews in GDC-WSIS alignments at the GA level. Speaking of overall reviews, the draft also envisions a combined review of Agenda 2030 and of outcomes of the WSIS-GDC joint implementation roadmap in 2030, as well as a WSIS+30 review in 2035.

Looking ahead

The Zero Draft sets the stage for intense negotiations ahead of the December 2025 High-Level Meeting. Member states and other stakeholders are invited to submit comments until 26 September. It then remains to be seen what a second version of the outcome document will look like, and which elements are kept, revised, or removed.

Follow the process with us on our dedicated WSIS+20 web page, where we will track key developments, highlight emerging debates, and provide expert analysis as the negotiations unfold.