Digital Watch newsletter – Issue 57 – February 2021

TRENDS

The top digital policy trends in February

Each month we analyse hundreds of unfolding developments to identify key trends in digital policy and their underlying issues. Here’s what mattered in February.

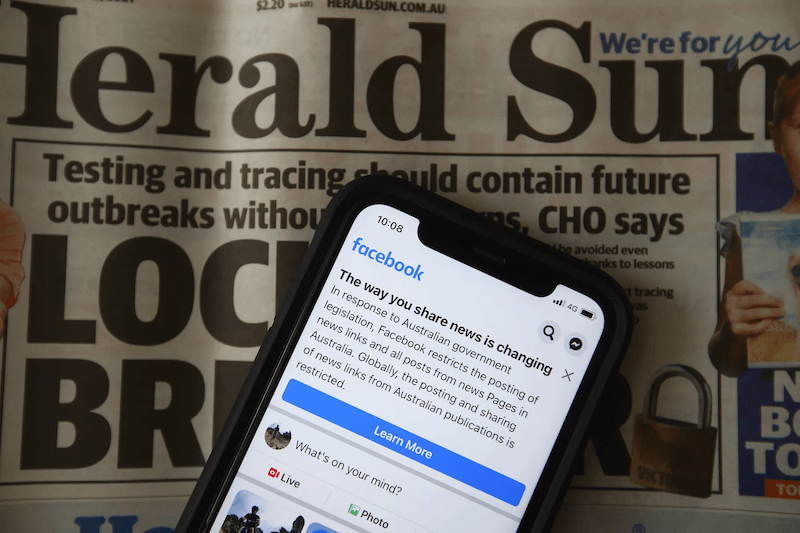

Rethinking media bargaining, one country at a time

With Australia’s media bargaining code entering into force, other countries have taken inspiration. It was not so much Facebook lifting its service ban that got countries debating new legislation to force platforms to pay for news content. Rather, it was Facebook’s (and Google’s) threat to boycott the country that prompted countries like Canada to react.

‘I must condemn what Facebook is doing’, Canadian Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault said during an online news conference. ‘What Facebook is doing in Australia is highly irresponsible and compromises the safety of many Australian people ... I suspect that soon we will have 5, 10, 15 countries adopting similar rules.’ Among the countries considering similar rules are Finland, France, and Germany, with Guilbeault already having met representatives from each.

Meanwhile, the EU will use the momentum around the Digital Services Act and Copyright Directive to shape tech companies’ obligations in news. The USA will also push ahead with new legislation. Congressman Ken Buck, a Republican sitting on the House of Representatives’ Judiciary Committee antitrust panel, said that a bipartisan group plans to introduce a bill in the coming weeks to make it easier for smaller news organisations to negotiate with Big Tech platforms.

Australia’s main motive for introducing legislation was to address unequal bargaining power between news media and platforms such as Google and Facebook. For their part, the companies argued that they already generate billions of free referrals to publishers on their platforms.

However, with Australia’s media bargaining code coming into effect, the companies’ argument is now a moot point. The Australian government has shown it is able to wield its normative power despite the companies’ threats to block their services in the country. Big Tech can now expect more governments to use their power, and if governments find they can indeed force the companies’ hand on media issues, they will be motivated to do so in other areas.

Gig workers: Indispensable yet unprotected?

‘When the pandemic hit European communities in March 2020, drivers were there to help safely transport tens of thousands of health workers while public transport services were reduced or suspended. As businesses were forced to close their doors and millions of people asked to stay at home, couriers provided an essential delivery service and a lifeline for local restaurants.’

This quote comes from Uber’s latest white paper, A Better Deal, which describes the company’s policy on the independent status of drivers and couriers working in the gig economy. Uber argues that ‘we need to do much more to ensure independent workers have access to benefits and protections when they need them most.’ The question is, what does ‘much more’ mean?

For Uber, it means: (a) retaining their status as independent contractors, as a precondition for being able to work flexibly and (b) helping them pay contributions towards a social safety net or a fund, which they can spend on the benefits or protections they want.

Contractors, however, hold a different view, and in some cases, these views have been confirmed by the courts. The UK Supreme Court is one of them (as was the Spanish Supreme Court back in September). In its 19 February judgement, the court said the drivers are workers and are entitled to a minimum wage and to annual leave.

The EU is also seeking to improve the status of gig economy workers (in line with the EU Commission chief’s 2019–2024 priorities), and has just launched a new public consultation.

It would have been much simpler if all these legal challenges and new laws pointed in the same direction. Yet, an ever-growing patchwork of regulations and policies continues to emerge. Most notably, voters in California said yes to Proposition 22, which has allowed gig economy companies to continue treating workers as independent contractors.

Although the outcome of Proposition 22 and the enormous amount of money Uber and Lyft (and others) spent on lobbying could somehow be linked, that same playbook does not appear to be in use elsewhere. Gig workers' place in the economy has been an issue for several years; COVID-19 has now shone a brighter light on a group of people who have become indispensable to society.

The rise of digital money

The use of cash has been in decline for years. E-commerce and mobile apps have made digital transactions a more preferred way of paying for goods and services.

The decline of cash is one of the reasons why a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) has been on the agenda for so many governments. China is getting close to implementation as it enters the final phase of its digital yuan project.

Private companies are getting involved too. In February, China announced that tech giants Tencent and Ant Group had entered the final phase of testing. The IMF has said that private-sector partnerships could be the key to CBDC’s survival.

Efforts are also underway by the G20, which maintains a specialised commission for determining rules around digital currencies. Although it is unclear whether China will announce its CBDC before a global agreement is reached, the country’s progress will put it at the cutting edge in shaping the development of other CBDCs.

On the cryptocurrency front, PayPal has given cryptocurrencies the green light on its platform. Company representatives said that the number of clients who have started using cryptocurrencies has surpassed their expectations.

Meanwhile, Tesla announced a US$1.5 billion investment in bitcoin, making it the biggest company in the world to hold the cryptocurrency on its balance sheet. Bitcoin has come a long way since its humble beginnings ten years ago.

BAROMETER

Digital policy developments in February

The digital policy landscape changes on a daily basis. Our aim is to decode, contextualise, and analyse ongoing developments, offering a digestible yet authoritative update. There’s more detail in each update on the GIP Digital Watch observatory.

Global IG architecture

decreasing relevance

The first preparatory meeting for IGF 2021 tackled theme selection, event format, and intersessional work.

Sustainable development

decreasing relevance

The World Bank has announced that it will allocate US$200 million to support digital transformation in Ethiopia and US$500 million to improve digital (and road) connectivity in Bangladesh.

France presented a strategy to bring together environmental and digital issues. Greece announced a biometric border management system. And the Scottish government allocated US$125 million for digital services and digital healthcare.

Security

increasing relevance

A Florida water facility was hacked, rendering the water unsafe to drink.

The OECD has published two reports on the security of digital products and how economic factors play a role, and how policymakers can address key challenges to security of smart products.

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child adopted General Comment 25, explaining why and how governments can protect children’s rights in the digital age. The annual Safer Internet Day highlighted the need to protect children online, as internet use among kids has continued to grow during COVID-19.

E-commerce and Internet economy

increasing relevance

China has introduced new anti-monopoly regulations to prevent tech giants from abusing their dominant market position.

The UK Supreme Court has ruled that Uber drivers are workers and enjoy workers’ rights. California’s Supreme Court declines to hear a case seeking to overturn the results of November’s Proposition 22 vote.

The planned sale of TikTok’s American operations to Oracle and Walmart has been postponed indefinitely. The government’s appeal in the case that blocked restrictions on TikTok has been delayed by the new administration.

Amazon is under investigation (again) in New York over an alleged scheme to inflate e-book prices and in India over preferential treatment of certain sellers and circumventing foreign investment rules. Epic Games filed an antitrust complaint against Apple in the EU while ByteDance filed an antitrust case against Tencent in China.

Digital rights

same relevance

The EU Council has adopted a position on the draft ePrivacy Regulation. The Brazilian Supreme Court has denied the right to be forgotten in the country.

Cambodia implemented a national internet gateway enabling the control and monitoring of online traffic.

The European Commission has issued a draft adequacy decision on personal data transfers between the EU and the UK.

A South African court declared bulk interception by the South African National Communications Centre unlawful unless explicitly stated in law.

Internet access is still heavily restricted in Myanmar, with sustained interruptions and night-time blackouts. Armenia has suffered an internet blackout amid political turmoil.

Content policy

increasing relevance

The Australian parliament passed the news media bargaining code that requires platforms to pay local publishers to link their content.

Twitter has the right to ban users for hate speech, a California appellate court ruled.

The Chinese government blocked the new social network Clubhouse.

Facebook will ban posts with false vaccine claims and will reduce the number of political posts on the news feeds of users in Canada, Brazil, Indonesia, and the USA. In response to the Myanmar coup, Facebook has banned Myanmar military and military-controlled state and media entities from its platform.

Jurisdiction and legal issues

same relevance

India has announced new rules to regulate social media platforms, streaming services, and digital news outlets.

After initially refusing to take down content by news media entities, journalists, activists, and politicians in India, Twitter has now fallen in line.

China has unveiled its ‘Action Plan for Building a High-Standard Market System’ as part of its intellectual property rights policy.

Infrastructure

same relevance

ICANN has launched a public consultation on a system for standardised access to domain name registration data. The Public Interest Registry (PIR) launched the DNS Abuse Institute.

A second submarine internet cable will land in Namibia.

Huawei is contesting the US Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) national security threat designation.

New technologies (IoT, AI, etc.)

same relevance

Nigeria’s central bank has banned banks from operating in crypto exchanges. The Indian government plans to ban private cryptocurrencies. Tesla announced a US$1.5 billion investment in bitcoin.

A Chinese company announced an operating system for quantum computers.

Germany will become the first country to legalise self-driving cars capable of hands-off operation, known as ‘Level Four’ autonomous driving.

In case you missed it...

The parachute for the Perseverance rover (whose drone runs on open source software Linux), that landed on Mars in February carried a colour-coded message written in binary code by systems engineer Ian Clark. The message spelled out NASA’s motto, ‘dare mighty things’.

EMERGING

Digital health passport: Adding to your travel checklist

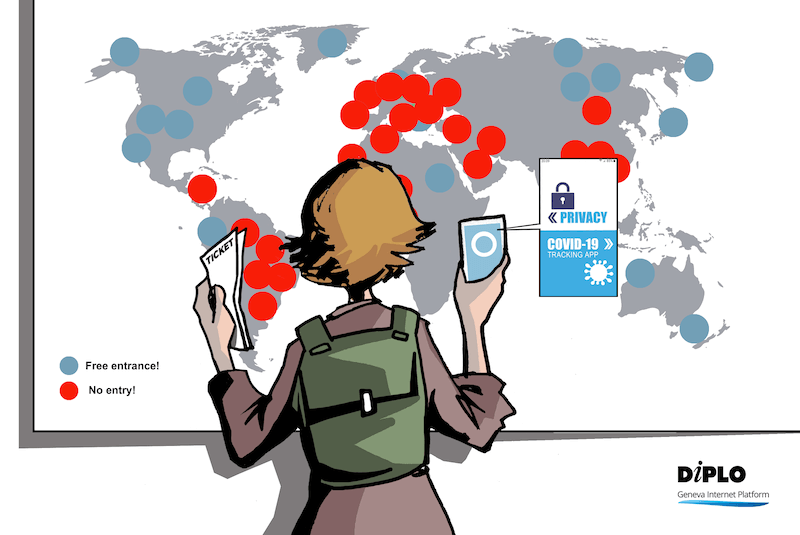

As many countries worldwide roll out COVID-19 vaccines, the efforts to develop and launch digital health passports have been accelerating in hopes that such tools will help countries reopen their borders … but at what cost?

Governments around the world put into place sweeping travel restrictions during the global COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020. Now that vaccines have been developed, digital health passports are being considered by some as an important tool to help countries lift international travel restrictions.

A digital health passport or immunity passport is an app or web-based service that stores and displays the result of a COVID-19 test or a vaccination record on a traveller’s mobile device. It could allow travellers to enter a country without the need to quarantine or self-isolate upon arrival, once the country’s authorities approve of the app in question.

Though details differ between apps, a traveller would need to register their test result or vaccine information in one of the apps, which would then generate a pass or QR code. Before passengers board a flight (that asks for and accepts the use of immunity passports), they will be asked to display their pass to verify that they have met entry requirements set by the destination country.

With the idea becoming more popular, some countries are also considering using the passes to allow people to go to certain places domestically. Israel, for instance, has launched a digital health pass to allow people entry into hotels and gyms upon proof they’ve received the vaccine.

The apps provide a more efficient alternative to current manual processes, and are immediate proof that someone has been inoculated. This could speed up the removal of restrictions and eventually restore air travel – and other forms of travel – to pre-COVID levels. An added benefit is that passport apps can help resolve issues around complex medical data by providing passengers with user-friendly information on testing or vaccination.

Yet, it would be too simplistic – and dangerous – to approve their use on these reasons alone.

What’s at stake?

Despite their obvious benefits, vaccines do not provide absolute immunity. Nor are they proof of safety for others, since a traveller may still transmit the virus. Immunity passports can therefore result in a false sense of reassurance.

Privacy issues and the related security risks present another challenge. The UK government’s announcement that it is exploring the concept of immunity passports (and proposing criteria for the development and use of passports) has attracted criticism from activists, who accused the government of wanting to create a system of controls meant to restrict people’s freedom of privacy.

The data itself needs to be verified and stored in a tamper-proof format. Security experts say that building confidence around this process requires transparency typically seen in open source software development. With more and more apps popping up, users will need to verify which apps are recognised in their country.

Relying exclusively on immunity passports can also lead to discrimination, since there are various reasons why a traveller might not have been (or cannot be) vaccinated.

Does this have any chance of succeeding internationally? Experts say it is feasible only if it is built on a trustworthy system and based on widely-accepted standards (such as the UK’s 12 criteria for developing immunity passports). Should immunity passports become widespread, they should only be used as a temporary measure as a way of getting places out of lockdown safely, experts warn.

Who’s in the game?

Efforts to develop digital health passports are pouring in from both the public and private sectors. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) announced in November 2020 that it is in the final phase of developing a digital health passport, called the IATA Travel Pass. In partnership with Estonia, the World Health Organization (WHO) is developing a similar digital health passport.

Australia and Greece have started issuing digital vaccine certificates to residents who have received two doses of vaccines on their respective government websites. Israel’s new pass is aimed at easing lockdowns and encouraging people to get vaccinated. Denmark will roll out its ‘digital corona passport’ this spring. Across the Baltic Sea, Sweden has also announced it will launch a digital health passport by summer.

A group of US tech companies – including Microsoft, Oracle, and Salesforce – have launched the Vaccine Credential Initiative to create an open source and standardised model of digital immunisation records for hospitals, pharmacies, and clinics that are administering COVID-19 vaccines. The Commons Project, a non-profit organisation supported by the World Economic Forum, is developing CommonPass, a digital health pass with a focus on privacy requirements.

DATA ANALYSIS

Mapping digital foreign policy strategies

Digital foreign policy is set to become prominent this year as countries (re)define and sharpen their approach. Although digitalisation has impacted foreign policy for years, it's only recently that foreign affairs ministries have stepped up their efforts to develop and communicate digital aspects in their foreign policy.

At the end of last year, Switzerland launched its Digital Foreign Policy Strategy 2021–24; this month, it was Denmark’s turn to publish its Tech Diplomacy 2021–2023 strategy. The two are among a handful of other countries pursuing comprehensive digital foreign policy strategies.

What is a comprehensive digital foreign policy?

This term refers to a policy which outlines a country's approach to digital issues and digitalisation as part of its foreign policy. Typically, this would link the digital policy work of a foreign affairs ministry with that of other ministries and stakeholders. Such a strategy would also outline digitalisation priorities, and how these priorities are pursued as part of the country's foreign policy.

Digital and foreign policy: Some approaches

Our data analysis on how countries are approaching digital issues in their foreign policy reveals four groups:

- Countries that have developed comprehensive digital foreign policy strategies

- Countries with foreign policy strategies that make a reference to digitalisation

- Countries with digital strategies that include foreign policy aspects

- Countries that communicate digital strategic priorities via the website of their foreign affairs ministry

Australia was one of the first countries to publish a comprehensive strategy – the Australian International Cyber Engagement Strategy – in October 2017, after which a progress report was released in 2019. France was also an early mover, with its 2017 Stratégie internationale de la France pour le numérique.

The Netherlands and Norway have published digital foreign policy strategies with a slightly narrower focus. The Dutch strateg. (2019) focuses on trade and development, while the Norwegian strategy (2018) focuses on digitalisation in the context of development.

Although only a handful of countries have launched comprehensive strategies, we can expect more countries to follow suit and publish their strategies this year.

We’re not saying that countries need comprehensive strategies in order to have an effective foreign policy with regard to digital issues and digitalisation. Countries that are considered active and important players in digital foreign policy, such as Canada, China, and Russia, have foreign policy strategies that make explicit references to aspects of digitalisation. Other influential countries, such as Brazil, Germany, and the USA, communicate priorities on their foreign ministries’ websites.

A closer look at the strategies

A comprehensive digital foreign policy strategy sends a clear sign that digitalisation is a foreign policy priority and sheds light on the approach and priorities of a country. It offers a window into understanding how digitalisation and foreign policy are conceptualised within the foreign ministry.

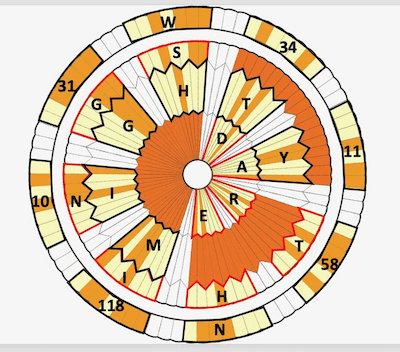

An easy way of detecting a country’s focus is through language: the use of prefixes is often linked to specific topics. For example, in the area of security, ‘cyber’ is the most prominent prefix. ‘Tech’ is often more rooted in discussion related to the business sector. And ‘online’ is more prominent in discussions on human rights. In addition, prefixes also reflect trends, such as Australia’s use of ‘cyber’ – which was a popular term that was used to refer to digital issues beyond security - when its 2017 strategy was drafted.

Our analysis of existing strategies shows that ‘digital’, by far, is the most prominent prefix. There are also two spikes worth noting. Denmark was one of the first countries to appoint a ‘tech ambassador’, hence the prominence of ‘tech’ in its strategy which has a particular focus on ‘tech diplomacy’. The Australian strategy’s use of ‘cyber’ is linked to the country’s approach to cybersecurity as a foundation for all other digital policy aspects. With regard to specific policies, development and data and privacy stand out in the Dutch and French strategies, while development and cooperation are priority areas in the Danish strategy. The Swiss strategy stands out for its comparatively stronger emphasis on data and privacy.

|

Switzerland (2020) |

Australia (2017) |

France (2017) |

Netherlands (2019) |

Denmark (2021) |

|

|

data & privacy |

135 |

19 |

76 |

98 |

7 |

|

ai/artificial intelligence |

53 |

0 |

8 |

19 |

1 |

|

security |

45 |

217 |

58 |

25 |

13 |

|

human rights |

39 |

83 |

30 |

16 |

9 |

|

governance |

60 |

67 |

26 |

1 |

3 |

|

development |

94 |

93 |

74 |

71 |

31 |

|

science |

28 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

economy/economic |

68 |

69 |

59 |

47 |

3 |

|

cooperation |

57 |

72 |

25 |

41 |

16 |

|

research/education |

40 |

22 |

24 |

24 |

5 |

|

health(care) |

16 |

5 |

2 |

11 |

3 |

|

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) |

6 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

0 |

Our analysis reveals nuance in terms of strategic priorities and approaches, as each strategy is written in a specific context and for a particular audience. At the same time, we also find commonalities. For example, It would be surprising if a country failed to mention cybersecurity or made no mention regarding the economy.

It will be interesting to observe to what extent other countries will follow in the footsteps of Australia, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Switzerland in terms of releasing comprehensive digital foreign policy strategies. What variations and strategic priorities will these strategies reveal?

For updates on this ongoing study, visit our dedicated page.

LEGAL

UK Supreme Court rules Uber drivers are workers

In February, the UK Supreme Court ended a six-year legal battle between Uber and a group of drivers – who had sued the company for failure to grant them certain workers’ rights – by deciding in favour of the drivers.

The driver you booked through Uber might have dropped you off with a smile, but that doesn’t necessarily reflect how he feels about his job. Although drivers and couriers are considered indispensable, legal proceedings in various jurisdictions have documented the requests made by thousands of drivers and couriers for better protections.

The UK Supreme Court’s February decision confirmed that of the Employment Appeal Tribunal and the Court of Appeal: The drivers are indeed workers, and are entitled to certain rights.

The case: Uber BV v Aslam

The case number: [2021] UKSC 5, on appeal from [2018] EWCA Civ 2748

The court: Court of Appeal of England and Wales

The date: Judgment delivered on 19 February 2021

The judgement

The Supreme Court reasoned and decided that:

(a) In the UK, there are three categories of employment:

- Traditional employment (workers within the meaning of Section 230(3)(a) of the Employment Rights Act)

- Self-employment

- ‘Worker’s contracts’ within the meaning of Section 230(3)(b), which according to the court falls somewhere in between. In this category, individuals provide their services, under an express or implied contract, to another party that is not a customer or client.

The main issue was whether drivers worked under contract for Uber, or whether their contract was with the passengers.

(b) The court determined that when it comes to the status of workers, the law superseded contracts (Uber argued the opposite). Therefore, it needed to analyse the status of the drivers regardless of what their contract says.

(c) The court ruled that Uber drivers fall within the third category: during the hours they are actively working with Uber, they are working for and under contract with Uber. The court reached its conclusion based on five factors, proving that Uber had the upper hand in negotiating with drivers:

- The price is fixed by Uber

- The contractual terms are dictated by Uber

- Uber has control over the driver’s acceptance to drive people

- Uber has control over the way drivers deliver their services

- The drivers cannot communicate with customers

(d) How does one determine which hours a driver is a worker? The court ruled that a driver is a worker when they 1) have the Uber app switched on, 2) are within the territory in which they are authorised to use the app, and 3) are ready and willing to accept trips.

(e) The court found that since the drivers operate under workers’ contracts for Uber, some rights apply to them too. The court ruled that the right not to be unfairly dismissed does not apply, as this is limited only to those people in traditional employment. However, Uber drivers are entitled to the traditional workers’ rights of a minimum wage and annual leave.

GENEVA

Policy discussions: Updates from Geneva

Numerous policy discussions take place in Geneva every month. The following updates are from February’s events. For other event reports, visit the Past Events section on the GIP Digital Watch observatory.

COVID-19 response and digital trust – 16 February 2021

The panel, organised by the Graduate Institute, the Centre for Trade and Economic Integration, and the Global Health Centre, discussed the privacy features of contact-tracing apps developed during COVID-19. Speakers also discussed current approaches to digital vaccine passports; just like contact-tracing apps, passports may present similar issues along with their own challenges.

6th Geneva Engage Awards – 18 February 2021

The sixth edition of the GIP’s Geneva Engage Awards recognised actors in International Geneva that use social media to effectively highlight the work carried out in Geneva in areas such as development, human rights, and digital issues.

Three categories of International Geneva actors were recognised for their social media outreach and online engagement, while a fourth award (introduced last year) acknowledged efforts in online participation.

This year’s award recipients were: the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in the International Organisations category; The New Humanitarian in the Non-Governmental Organisations category; and the Permanent Delegation of the European Union in the category for Permanent Representations to the UN in Geneva. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) received an award for its efforts in creating innovative and effective approaches for conducting remote meetings. Read the data analysis report.

IGF 2021 First Open Consultations and MAG Meeting – 22–24 February 2021

The Internet Governance Forum’s (IGF) Multistakeholder Advisory Group (MAG) met online to gather feedback from the community in open consultations and to move forward with its preparations for IGF 2021, planned for December in Katowice, Poland. Participants also discussed how to improve the IGF, including aspects such as the event format and the intersessional work.

The most debated point was on how to establish the multistakeholder high-level body proposed in the Secretary-General’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation. The UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) and the Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Technology will organise further consultation processes. This was welcomed by several countries including the USA and Canada. Others, including Germany and Switzerland, highlighted the rich consultations that have already taken place and advocated for swift action in implementing the high-level body. In an open letter to the UN Secretary General,16 global and national civil society organisations also urged him to stop the formation of the body.

The MAG meeting also focused on best practice forums (BPFs), working groups, and themes for the next IGF. A new BPF on environmental data was proposed along with requests for the BPFs on cybersecurity, gender and digital rights, and local content to continue this year. For the first year, the new policy network format will kick off with the Policy Network on Environment and Digitalisation. A Policy Network on Meaningful Access was also proposed.

The new working group on hybrid meetings presented its plans and co-organised an informal networking event to showcase its experiments with online platforms. A working group on communications was also proposed, possibly to be integrated with the 2020 working group on outreach and engagement.

UPCOMING

On our radar: Global digital policy events in March

Upcoming events: Are you tuned in?

Learn more about upcoming digital policy events around the world and use DeadlineR to remind you about important dates and deadlines.