OEWG Chair releases Zero Draft and Rev 1 of the Final Report, setting stage for final talks

The report includes concrete actions and cooperative measures to address ICT threats and captures concrete progress made at the OEWG to promote an open, secure, stable, accessible and peaceful and interoperable ICT environment.

The Chair of the Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) on the security of and in the use of information and communications technologies in 2021–2025 released the Zero Draft of the OEWG Final Report, which was then followed by the revised version of the draft Final Report (Rev.1). This drafts were proposed by the Chair, and will serve as the basis for further negotiations at the OEWG’s eleventh substantive session in July 2025. They provide a comprehensive overview of the progress made during the OEWG’s mandate, outlining key proposals, discussions, and potential areas for future work on ICT security within the context of international peace and security. The report is expected to be adopted at the OEWG’s eleventh substantive session in July 2025.

States reaffirmed the consensus reached in the OEWG’s first, second and third Annual Progress Reports, the 2021 OEWG report, and earlier GGE reports (2010, 2013, 2015, 2021). These documents form a cumulative and evolving framework for responsible state behaviour in the ICT domain, including 11 voluntary norms and measures for confidence-building, capacity-building, and cooperation. States reiterated that international law, particularly the UN Charter, applies to the ICT environment.

The draft highlights that the OEWG addressed its mandate in a balanced way, advancing common understandings and the implementation of prior commitments. States acknowledged the sustained engagement of stakeholders and the key role of regional and sub-regional organisations in supporting implementation.

Existing and potential threats

States expressed growing concern over intensifying ICT threats amid a challenging geopolitical climate. They noted the development of military ICT capabilities and the increasing use of ICTs in conflicts. Concerns extended to malicious activities targeting critical and civilian infrastructure, undersea cables, orbit communication network, space-based networks, industrial systems, operational technology, 5G, IoT, cloud services, VPNs, and firewalls. Serious concern was expressed regarding malicious ICT activity targeting international and humanitarian organisations, including their in-country missions. A worrying increase in states’ malicious use of ICT-enabled covert information campaigns to influence another state’s processes, systems and overall stability was also noted.

Ransomware emerged as a key threat, with States warning of its growing scale, severity, and impact on international security. Wiper malware and trojans, phishing, man-in-the-middle and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) were also specifically underlined. States called for a comprehensive response—targeting ransomware actors, their tools, and illicit financial flows—and noted the need for a human-centric approach to mitigate harms. States also flagged rising threats from cryptocurrency theft.

A particular emphasis was made on the challenges of the market for spyware and intrusion tools. States noted the growing availability of commercial ICT intrusion tools and vulnerabilities on the dark web. Importantly, the text also calls for meaningful action by the states, warning that without it, these threats are expected to increase as the market grows and diversifies further. New and emerging technologies, particularly AI and quantum computing, were considered double-edged, offering security benefits and expanding the attack surface. AI-driven attacks and misuse of large language models (LLMs) for generating malware and deepfakes were noted as reducing barriers to malicious activity. States stressed the need for secure-by-design approaches, post-quantum cryptography, and strong data protection.

States continued to express concern that a lack of awareness of existing and potential threats and a lack of adequate capacities to detect, defend against and/or respond to malicious ICT activities may make them more vulnerable. States encouraged enhanced awareness, capacity-building, public-private partnerships and international cooperation, especially among CERTs and CSIRTs.

Rev 1 introduces several changes to the original draft. It removes reference to ICTs being used alongside conventional weapons in conflicts from paragraph 15. This could be due to concerns that such language implicitly points fingers or legitimises military cyber operations. Reference to the blurring of lines between cybercrime and threats to international security was removed from paragraph 16, perhaps as it may have been seen infringing on domestic jurisdiction, which is a long-standing tension in cyber discussions.

The language on cryptocurrency in paragraph 24 has been strengthened, stating that cryptocurrency theft and its use in financing malicious ICT activities impact international peace and security, rather than potentially impacting international security.

Proposed text related to spyware and intrusion tools has been expanded in Paragraph 25 to stress the risks of dissemination of ICT intrusion capabilities, especially if used inconsistently with the framework for responsible state behaviour, and highlights the need for safeguards and oversight of ICT intrusion capabilities market. It also adds a new sentence on ensuring that such measures do not hinder lawful use of ICT tools, particularly by developing countries. This new sentence strengthens the connection of this paragraph with paragraph 34(h) on norms.

The report’s recommendations

- States to continue exchanging views on existing and potential threats to security in the use of ICTs in the context of international security at the future permanent mechanism.

- States to continue focused discussions on possible cooperative measures to address these threats, aware that all states’ commitment to the framework for responsible behaviour in the use of ICTs is fundamental to addressing threats.

Norms, rules, and principles

States affirmed that voluntary, non-binding norms of responsible behaviour help reduce risks to international peace and stability by improving predictability and preventing misperceptions. Such norms reflect the international community’s expectations and standards regarding states’ use of ICTs and allow the international community to assess states’ activities.

States also encouraged whole-of-government coordination and awareness-raising on these norms, acknowledging the need to consider technical gaps, differing national systems, and regional contexts.

States underlined the importance of norms (c), (d), (f), (g), (h), and (i).

States stressed the need to protect critical infrastructure (CI) and critical information infrastructure (CII) from ICT threats, through measures such as voluntary designation of CI and CII, comprehensive risk assessments, ICT awareness and training, and the development of relevant national regulatory requirements and guidelines. States proposed creating common templates for responding to ICT incidents affecting CI/CII to facilitate effective international cooperation.

Emphasis was placed on strengthening supply chain integrity through establishing policies and programmes to promote the adoption of good practices by suppliers and vendors of ICT equipment and systems, enhancing quality and promoting choice, exchanging best practices and developing globally interoperable standards for supply chain security.

States proposed measures to prevent the illegitimate and malicious use of commercially available ICT intrusion tools by ensuring their development, dissemination, purchase, export, and use align with international law. They stressed the importance of embedding security-by-design in ICT products, prioritising security over rapid market release. States also highlighted the essential role of the private sector in maintaining supply chain integrity and preventing the spread of malicious tools.

States proposed the adoption of the Voluntary Checklist of Practical Actions as a reference document for the voluntary implementation of voluntary, nonbinding norms. The checklist contains voluntary, practical actions for implementing norms. These actions are divided into actions at the national level and actions requiring international cooperation.

Targeted ICT security capacity-building programs are important to address implementation challenges and capacity gaps. Technical differences, diverse national systems, and regional specifics should be considered when using the voluntary checklist.

New norms for ICT use could be developed over time, states affirmed, and new norms can be developed alongside implementing existing ones. States proposed continuing discussions on additional norms at the future permanent mechanism, including compiling and sharing a list of proposed rules and principles to support ongoing study and dialogue.

The Rev. 1 Draft introduces several changes to the initially published Zero draft. It strengthens the clarity of the text, such as in paragraph 34(b) by including the term ‘implementation’ in the context of coordination on agreed norms, and in paragraph 34(f) by inserting ‘in accordance with the national legislation of States’ in the context of cooperation between government authorities and CI/CII operators.

The new version also removes detailed recommendations—such as the development of voluntary templates for requesting assistance by another state whose CI is under cyber-attack, and the inclusion of specific procedural elements— were removed from paragraph 34(e). This shift avoids prescribing how states should operationalise cooperation, instead allowing them greater discretion in identifying appropriate mechanisms such cooperation, and possibly shifting discussions about details to the future permanent mechanism.

The reference to ‘trusted exchanges between relevant government authorities and CI/CII operations’ has been replaced with ‘voluntary exchanges’ in paragraph 34(f) and thus a new language softens the expectation that states must take specific implementation steps, reinforcing that the norms are voluntary and non-binding.

The revised text of paragraph 34(h) proposes that the development, dissemination, purchase, export or use of ICT intrusion tools should be – but also facilitated or transferred – ‘for lawful purposes’ instead of ‘consistent with international law.’ While ‘international law’ refers to a recognised set of binding legal norms, ‘lawful purposes’ sound more flexible and can be interpreted according to national contexts. This change may help avoid political sensitivities tied to differing interpretations of international law, while still emphasising that actions related to ICT intrusion tools must be legally justified. However, it can also weaken the normative clarity by moving away from an internationally agreed-upon legal benchmark.

A new paragraph 34(n) was added, where the complementary nature of cyber norms in relation to existing international law is highlighted. It clearly states that norms do not replace or override binding legal obligations, but instead offer non-binding guidance on responsible state behaviour in the use of ICTs. This clarification affirms state sovereignty and ensures norms are not seen as limiting lawful action. This wording was actually taken ad verbum from paragraph 25 of the OEWG report of 2021. The original wording is now, however, extended by the explicit acknowledgement that the framework of responsible state behaviour that OEWG contributed to provides a foundation for the future permanent mechanism. This addition can be understood as a guarantee that the framework will be the foundation of the future permanent mechanism.

The report’s recommendations

- States to continue exchanging views at the future permanent mechanism on rules, norms and principles of responsible State behaviour in the use of ICTs

- The UN Secretariat to compile a non-exhaustive list of proposals from states on rules, norms and principles of responsible behaviour of states and circulate that list to delegations.

- States agree to adopt the Voluntary Checklist of Practical Actions for the implementation of voluntary, non-binding norms of responsible state behaviour in the use of ICT

Rev 1 rewrites paragraph 36 in the recommendations section and explicitly references proposals from both ‘States and stakeholders,’ which would be positively met by many in the international community as it reinforces a multistakeholder approach to norm development and implementation—an important recognition of the diverse actors contributing to cyber-stability efforts.

International law

States reaffirmed that the core principles of international law, including sovereignty, sovereign equality, and the peaceful settlement of disputes, as outlined in Articles 2(3), 2(4), and 33(1) of the UN Charter, apply to cyberspace. In the Zero Draft, States reaffirmed that ICT operations may amount to a use of force under Article 2(4) of the UN Charter if their scale and effects are comparable to non-ICT operations rising to the level of a use of force. Even when not rising to that level, ICT activities could still be contrary to other principles of international law, such as state sovereignty and non-intervention. States emphasised that no state should interfere—directly or indirectly—in another state’s internal affairs through the use of ICTs.

States also made additional concrete, action-oriented proposals on international law:

- States proposed that discussions on international law could continue to benefit from expert briefings, such as from the International Law Commission or academia, as appropriate.

- States proposed that the application of international law in the use of ICTs could be discussed further at the future permanent mechanism. States suggested that areas of an in-depth study could be: States’ obligations regarding respect for territorial sovereignty; the due diligence obligations of a state in the use of ICTs; the obligations of non-state actors in the use of ICTs under international law; and how CI and CII, as well as data, are protected under international law.

- States noted the importance of exchanging national positions to build common understandings.

- States continued to underscore the urgent need to continue capacity-building initiatives on international law. Such initiatives could include: Workshops, conferences and the exchanging of best practices; Online and in-person training courses and modules as well as online resource libraries; Strengthening collaboration with academics, civil society and the private sector to tailor international law capacity-building programmes; Partnering with regional and sub-regional organisations to implement capacity building initiatives that address localised needs.

Revision 1 strengthens multilateral aspects of the future permanent mechanism, and signals weakening of consensus on the issues included in the original Zero draft.

The revision removes text on what constitutes the use of force (paragraph 40 c)), leaving the discussion on conduct using ICTs and its relation to a violation of the prohibition on the threat or use of force (paragraph 40 e)) to the future permanent mechanism. This indicates the lack of consensus on the definition on what may constitute the use of force in cyberspace.

The revision refocuses on state perspectives on how international law applies in the use of ICTs (paragraph 40 of the Zero draft, paragraph 41 of the Rev. 1) leaving out the statement by the Inter American Juridicial Committee.

The revision keeps reference to the statement by the Russian Federation and co-sponsors that was opposed by some states because it does not provide views on how international law applies in cyberspace. The revision also kept references to the Common African Position, Resolution 2 of the 34th ICRC Conference, and Declaration by the European Union and its Member States on a Common Understanding of International Law in Cyberspace, adding a statement on IHL by a group of states from 1 March 2024, and of the cross-regional group of states from 21 May 2025.

Additionally, Rev 1 removed references to proposed in depth areas of study on how international law applies to the obligations of states as they pertain to respect for the territorial sovereignty of states; the due diligence obligations of a state in the use of ICTs; the obligations of non-state actors in the use of ICTs under international law (paragraph 41 b) of Zero draft, paragraph 42 b) of Rev. 1).

The report’s recommendations

- States to continue to engage in focused discussions at the future permanent mechanism on how international law applies in the use of ICTs

- States to continue to voluntarily share their national views and positions on how international law applies to the use of ICTs.

- States in a position to do so to continue to support, neutrally and objectively, additional efforts to build capacity in the areas of international law

In recommendations (paragraph 42 of the Zero Draft, paragraph 43 of the Rev. 1), the text refers to what will be discussed within the international law topic in the future permanent mechanism. The revised text now omits proposals and papers on the topic of international law as submitted by states to the UN Secretariat in the course of the work of the OEWG 2021-2025, leaving the future permanent mechanism with a much narrower scope for discussion. Additionally, the Rev 1 removed references to proposed in depth areas of study on how international law applies to the obligations of states as they pertain to respect for the territorial sovereignty of states; the due diligence obligations of a state in the use of ICTs; the obligations of non-state actors in the use of ICTs under international law (paragraph 41 b) of Zero draft, paragraph 42 b) of Rev. 1).

Confidence-building measures

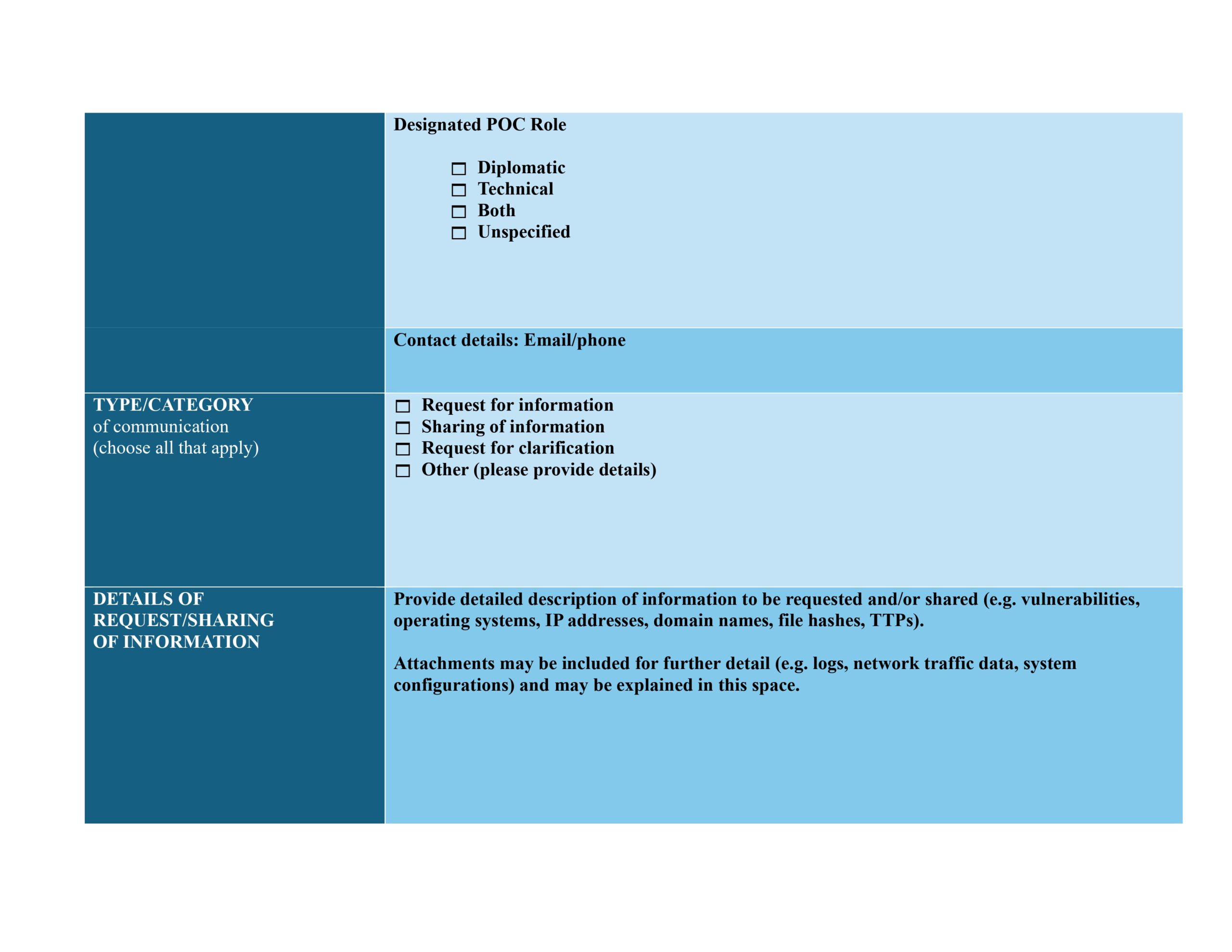

Countries highlighted the importance of continuing to expand and operationalise the Global Points of Contact (POC) Directory, and supported its seamless transition from the OEWG to the future permanent mechanism on ICT security.

They also stressed the need to put into practice the ‘Initial List of Voluntary Global Confidence-Building Measures’ from the third Annual Progress Report. These include:

- Nominating national Points of Contact to the Global POC Directory, and operationalising and utilising the Global POC Directory (CBM 1)

- Continuing to exchange views and undertaking bilateral, sub-regional, regional, cross-regional and multilateral dialogue and consultations between states (CBM 2)

- Sharing information, on a voluntary basis, such as national ICT concept papers, national strategies, policies and programmes, legislation and best practices (CBM 3)

- Encouraging opportunities for the cooperative development and exercise of CBMs (CBM 4)

- Promoting information exchange on cooperation and partnership between states to strengthen capacity in ICT security and to enable active CBM implementation (CBM 5);

- Engaging in regular organisation of seminars, workshops and training programmes on ICT security (CBM 6);

- Exchanging information and best practices on protecting CI and CII (CBM 7);

- Strengthening public-private sector partnerships and cooperation on ICT security (CBM 8).

States encouraged practical implementation steps such as dialogue, information-sharing, and best practices exchange. States reaffirmed the progress made so far and reaffirmed the need for continued discussions on the development and implementation of CBMs in the future mechanism.

States also welcomed the ‘Template for Communication – Example provided by the Secretariat pursuant to A/79/214’, annexed to the Final Report as Annex B.

The Rev. 1 Draft introduces several changes to the initially published Zero draft, and it replaces the word ‘expanding’ in paragraph 47(b) with the word ‘developing’ in relation to the Global POC directory and thus narrows the focus, probably reflecting more realistic expectations. It may also signal that the immediate priority is stabilisation and functional development rather than broadening its scope or user base of the Global POC directory.

The wording ‘on ICT security in the context of international security’ was deleted in paragraph 47(b) in relation to the future permanent mechanism, which now probably shifts the focus to the practical and operational aspects of the Directory and softens the geopolitical framing, given the ongoing disagreements between the delegations on the status of the regular institutional dialogue.

The more positive and affirming term ‘welcomed’ was replaced with the more neutral ‘noted’ in paragraph 47(e), and the new version thus avoids suggesting unanimous endorsement of the template. It reflects a more cautious or reserved tone, which signals that differing views on the usefulness or content of the template still exist. At the same time, a new sentence was added to show states’ openness to continued dialogue and refinement of the communication template. The phrases ‘timely, objective’ and ‘disclosure’ of the ICT vulnerabilities were also deleted in paragraph 47(f), which significantly simplifies the whole text in the paragraph. The new version avoids technical or normative language, likely to make the sentence more neutral and widely acceptable.

The report’s recommendations

- States to continue exchanging views at the future permanent mechanism on the development and implementation of CBMs

- States to continue the further development and operationalisation of the Global POC Directory at the future permanent mechanism

- The UN Office of Disarmament Affairs, in its capacity as manager of the Global POC Directory, is requested to convene regular simulation exercises , to allow representatives from states to simulate the practical aspects of participating in a POC directory,

- States agree to adopt the ‘Template for Communication – Example provided by the Secretariat pursuant to A/79/214’

- States are encouraged, on a voluntary basis, to continue to share national views on technical ICT terms and terminologies to enhance transparency and understanding between states

Rev 1 amends the recommendations section in paragraph 48 by adding a new sentence to encourage iterative development and dialogue regarding the Global POC Directory, rather than endorsing its current state as final. In paragraph 50, the new version replaces ‘adopt’ with ‘continue discussing’ regarding the communication template and thus recognises that not all states may be ready to endorse the template.

Capacity building

States reiterated their commitment to the ICT security capacity-building principles outlined in the 2021 OEWG report, stressing the need to further embed these principles into practical capacity-building programmes. They emphasised gender-responsive approaches, advocating for the integration of gender perspectives into national ICT policies and the development of tools to identify related gaps.

Recognising that capacity-building must be tailored to individual national contexts, states supported aligning efforts with a recipient country’s self-assessed ICT security status.

Long-term sustainability was highlighted, with calls to invest in human resources, institutions, and infrastructure. Standardised training and curriculum development were proposed to ensure consistent technical capacity across states. Mentorship programmes were also suggested to provide ongoing support, especially in enhancing CERTs and CSIRTs’ expertise in areas such as forensic analysis and incident response.

States welcomed the UN Secretariat’s proposal for a Global ICT Security Cooperation and Capacity-Building Portal (GSCCP). States proposed that GSCCP could initially serve as: (a) the official website of the future permanent mechanism; (b) a central location for providing practical information on ICT security events to foster the active participation of States; and (c) a platform to facilitate the sharing of information relating to best practices and capacity-building. The Global POC Directory could also be integrated into the GSCCP.

Additional proposals included a needs-based capacity-building catalogue and a UN CyberResilience Academy within UNIDIR to offer solution-focused support, particularly for less-resourced States.

The draft report also recognises the UN Secretariat’s proposal for the development of a UN voluntary fund to support cyber capacity-building and participation of developing countries in the future process. The fund should build on existing initiatives, while avoiding duplication of efforts.

The Rev. 1 draft introduces several changes to the initially published Zero draft and it adds ‘voluntary’ in paragraph 52(c) in the context of standardization of curriculum or scope of technical ICT security capacity-building programming. The new text thus signals that any effort toward harmonisation or standardisation of training or curricula should not be imposed, but rather undertaken by mutual agreement among states.

Paragraph 52(c) was amended with a new sentence to acknowledge the growing role of South-South and triangular cooperation in the field of ICT security capacity-building. The new sentence also makes clear that these approaches complement rather than replace traditional North-South cooperation.

The new sentence in paragraph 52(d) introduces concrete, actionable proposals for how states could enhance cooperation between CERTs and CSIRTs—key national and regional cybersecurity actors. The new language highlights technical-level cooperation, and by including developing countries explicitly, the text also reflects broader UN goals on inclusive capacity building.

The word ‘coordination’ was replaced with the word ‘cooperation’ in paragraph 52(e) to probably imply a more mutual, voluntary, and collaborative relationship, rather than suggest a more structured or hierarchical process. The new version also adds ‘with representation of high-level government officials or relevant governmental and non-governmental experts’ in paragraph 52(k) to broaden the scope of participants in regular international security discussions to also include non-governmental experts. The amendment acknowledges the valuable contributions of civil society, academia, and technical communities.

The report’s recommendations

- States to continue focused discussions on capacity-building efforts at the future permanent mechanism

- States to convene regular High-level Global Roundtables on ICT security capacity-building under the auspices of the future permanent mechanism to allow for strategic as well as action-oriented discussions on ICT capacity-building

- States agree to establish a dedicated Global Information and Communication Technologies Security Cooperation and Capacity Building Portal.

- States agree to establish a sponsorship programme administered by the UN Secretariat, funded exclusively by voluntary contributions to support the participation of developing countries in the meetings of the future permanent mechanism.

- States agree to continue discussions at the future permanent mechanism on the development and operationalisation of a UN voluntary fund to support the capacity-building of states on the security of and in the use of ICTs.

- States in a position to do so are encouraged to continue to support capacity-building programmes, including in collaboration, where appropriate, with regional and subregional organisations and other interested parties and stakeholders.

In paragraph 58, a new sentence was added to emphasise that capacity-building efforts should be demand-driven, reflecting the specific needs and priorities of developing countries rather than applying one-size-fits-all solutions. By including ‘respective national ownership and sovereignty’, the new text aligns with broader UN principles of fairness, inclusion, and state-led cooperation.

Regular institutional dialogue

States continued to deliberate on the establishment of a regular institutional dialogue and reaffirmed their commitment to ensuring a smooth transition from the OEWG to the future permanent mechanism. They agreed that the new mechanism would support the ongoing implementation and further development of existing initiatives launched under the OEWG 2021–2025 and earlier processes. This includes, among others, the Global POC Directory and the Global Roundtable on ICT security capacity-building.

The report’s recommendations

- States agree to establish the future permanent mechanism in accordance with (a) the elements as agreed in Annex C of the third APR and as endorsed in General Assembly Resolution 79/237.

- States agree that the future permanent mechanism will be established according to the additional elements outlined in Annex III of the Final Report, which addresses thematic groups and stakeholder engagement.

Additional elements regarding the dedicated thematic groups

The work of dedicated thematic groups (DTGs) will aim to build on and complement the discussions in the substantive plenary sessions by providing the opportunity for more detailed and action-oriented discussions.

Each DTG meeting may feature expert briefings, in-depth thematic discussions on a rotating agenda, and consideration of concrete measures to advance collective objectives.

At its organisational session in March 2026, the permanent mechanism would establish three DTGs.

- The first would focus on action-oriented measures to enhance state resilience and ICT security, protecting critical infrastructure, and promoting cooperative action to address threats in the ICT environment.

- The second group would continue the discussions on how international law applies to the use of ICTs in the context of international security.

- The third group would address capacity-building in the use of ICTs, with an emphasis on accelerating practical support and convening the Global Roundtable on ICT security capacity-building on a regular basis.

Each DTG will be led by two co-facilitators, appointed by the Chair of the permanent mechanism in consultation with states, with a two-year term. The groups may meet jointly to foster holistic discussions across thematic areas. Co-facilitators will provide regular updates to the plenary sessions. Dedicated thematic groups could also agree by consensus to submit action-oriented draft recommendations, if any, to the permanent mechanism at its substantive plenary sessions.

Interestingly, DTGs will convene for ‘at least one day per year’, which seems rather a short time for discussions. It will be scheduled sequentially immediately prior to or immediately following substantive plenary sessions as plenary sessions to ensure coherence. Meetings will be held in a hybrid format to promote inclusivity, with in-person participation encouraged and proceedings broadcast via UN WebTV. These meetings will be considered informal. Additional sessions may also be held during intersessional periods if necessary. The DTGs will operate until the first Review Conference, which will determine their continuation and scope for the following four-year cycle. The permanent mechanism may also establish additional ad-hoc DTGs for focused, time-bound discussions on specific topics, provided there is consensus among states.

Rev 1 clarifies that it will be a global, inclusive and universal mechanism in which states will negotiate on ICT security under the UN auspices. Inclusiveness signals openness to all states but also other actors, while universality signals that no other process should run in parallel.

Rev 1 also clarifies, in paragraph 7, that the relevant experts who will brief DTGs will be drawn from a pool of experts nominated by states—an addition likely aimed at promoting fairness, regional diversity, and balanced representation, but also strengthening the role of states with regard to involving other stakeholders. It is also likely in reply to Joint Paper on Dedicated Thematic Groups of the Future Permanent Mechanism on ICT-security submitted by a group of like-minded States (Belarus, Venezuela, DPRK, Iran, China, Cuba, Nicaragua, Russian Federation, Eritrea, Zimbabwe), which notes that the criteria and mechanism for external expert selection is lacking.

Rev 1 paragraph 7 also clarifies that dedicated groups will not be making decisions on possible action-oriented measures, but rather updates and draft recommendations. This was likely included to address concerns that not all states can participate in the DTGs due to limited staff or budgets, ensuring that decisions aren’t shaped solely by a more resourced minority.

It also adds new language on how the Chair will, in consultation with the respective co-facilitators of each DTG, prepare guiding questions prior to each dedicated thematic group meeting, which delegations will be requested to address. This addition signals a top-down approach to agenda-setting, which could be helpful in ensuring that discussions across all DTGs remain structured and coherent under the Chair’s overarching guidance.

Per Rev 1, DTG 1 will focus on action-oriented ways to enhance state resilience and ICT security. While the text still acknowledges that the group will draw on the pillars of the framework for responsible state behaviour in the use of ICTs, Rev 1 underlines that it will draw on all pillars. However, references to the group protecting critical infrastructure and promoting cooperative action to address threats in the ICT environment were removed. Instead, the group will be addressing ‘existing and potential threats, and [by] enhancing ‘concrete actions and cooperative measures’ such as rules, norms, and principles of responsible State behaviour, and confidence-building measures.’ This addition is particularly relevant as states disagreed on the number and scope of the DTGs, with some insisting that the composition of the DTGs should be based on the five pillars (threats, norms, rules and principles, international law, confidence-building measures, capacity-building). With this new text, DTG 1 would be rather overarching.

DTG 2 will to continue discussions on how international law applies to the use of ICTs in the context of international security, but Rev 1 clarifies it will be done ‘in accordance with the agreed functions and scope of the permanent mechanism contained in paragraphs 8 to 11 of Annex C of the third APR.’ An important reminder is that paragraph 9 of Annex C of the third APR notes that the future permanent mechanism will ‘further consider the development of additional legally-binding obligations.’ As this has been a long-standing point of contention, some states likely saw this clarification as essential to protect a hard-earned concession.

Rev 1 adds that any delegation may request a review of the number and scope of the dedicated thematic groups at the third substantive session, after two years of the mechanism’s operation, to ensure their effective functioning. This was likely included to ease current disagreements over the proposed number and scope of the dedicated thematic groups, allowing states to adopt the report as it stands while offering reassurance that changes can still be made after three years if needed.

Paragraph 15 has been heavily edited and now clarifies that action-oriented draft recommendations made by DTGs will be transmitted to the permanent mechanism at its substantive plenary sessions by the co-facilitators of each DTG in consultation with states. It removes, however, the reference that the transmission of such draft recommendations depends on consensus. It also removes the text stating that ‘draft recommendations (if any) of the dedicated thematic groups can be agreed on a provisional basis by silence procedure for transmission to the substantive plenary sessions.’ These edits leave ambiguity as to the process of transmitting draft recommendations to the plenary sessions, as they may imply that draft recommendations can move forward even without full agreement.

Additional elements regarding stakeholders’ participation

The permanent mechanism will engage non-governmental stakeholders—such as businesses, NGOs, and academia—in a structured, ongoing, and meaningful way.

Accredited stakeholders will be able to attend key sessions, submit written inputs, and deliver oral statements during dedicated stakeholder sessions. They may also speak after member states, time permitting and at the Chair’s discretion. Participation is consultative only—stakeholders would engage in a technical and objective manner, and their contributions ‘shall remain apolitical in nature’. Negotiation and decision-making are exclusive prerogatives of member states.

NGOs with ECOSOC consultative status may express their interest in participating in the mechanism’s plenary sessions and review conferences by informing the Secretariat. Other relevant and competent stakeholders (beyond those with ECOSOC status) can also apply for accreditation. Accreditation will be granted on a non-objection basis and remain valid for each five-year cycle, with applications accepted annually.

If a member state objects to accrediting a stakeholder, it must inform the Chair and may voluntarily share the general reason for the objection. The Chair will then consult informally with all member states for up to three months to try to resolve the concern and facilitate accreditation. After the consultations, if the Chair believes consensus has been reached, the Chair may propose confirming the accreditation. If consensus is not yet possible, the Chair will continue informal consultations; The Chair may re-introduce accreditation of certain applicants again, based on a sense that consensus may appear.

The Chair will also hold informal or virtual meetings with stakeholders during intersessional periods. Finally, this stakeholder engagement model is unique to the permanent mechanism and does not set a precedent for other UN processes.

While Rev 1 didn’t make any significant changes in this section, more tensions are expected on the topic of stakeholder engagement.

The Joint Paper on Dedicated Thematic Groups of the Future Permanent Mechanism on ICT-security submitted by a group of like-minded States (Belarus, Venezuela, DPRK, Iran, China, Cuba, Nicaragua, Russian Federation, Eritrea, Zimbabwe) notes that these states are committed to the determination of stakeholder participation modalities within the future permanent mechanism by consensus on the basis of the OEWG modalities adopted in April 2022.

Per these modalities, accredited stakeholders may attend formal OEWG meetings without addressing them, speak during a dedicated stakeholder session, and submit written inputs for the OEWG website. Other relevant stakeholders may also apply by providing information on their purpose and activities; they may be invited to participate as observers, subject to a non-objection process. A state may object to the accreditation of specific non-ECOSOC-accredited organisations, and must notify the OEWG Chair of its objections. The state may, on a voluntary basis, share with the Chair the general basis of its objections.

The joint paper explicitly states ‘we doubt that there is any added value in engaging stakeholders within the dedicated thematic groups, which are envisaged to provide a venue for governmental experts to participate in focused discussions’.

However, a much different position on both issues is outlined in paper titled ‘Practical Modalities for Stakeholders’ Participation and Accreditation Future UN Mechanism on Cybersecurity,’ submitted on behalf of Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Chile, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, the Dominican Republic, Estonia, the European Union, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Kiribati, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Republic of Korea, the Republic of Moldova, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom..

On accreditation, this group notes that a state may object to the accreditation of specific non-ECOSOC-accredited organisations. However, the notice of intention to object shall be made in writing and include, separately for each organisation, a detailed rationale for such objection(s). One week after the objection period ends, the Secretariat will publish two lists: one of accredited organisations and another of those with objections, including the objecting state(s) and their reasons. These lists will be made public. At the next substantive plenary session, any state that filed an objection may formally oppose the accreditation. If the Chair considers that every effort to reach an agreement by consensus has been exhausted, a majority vote of members present and voting may be held to decide on the contested accreditations, following the Rules of Procedure of the UN General Assembly.

This group has proposed broader participation rights for stakeholders in the future mechanism. Their proposal includes:

- Enabling Chairs (or Vice Chairs) of thematic groups to invite stakeholders to submit written reports, give presentations, and provide other forms of support.

- Allowing stakeholders to deliver oral statements and participate remotely in plenary sessions, thematic groups, and review sessions.

- Permitting non-accredited stakeholders to attend plenary sessions silently.

- Granting the Chair (or Vice Chairs) the authority to organise technical briefings by stakeholders and states during key sessions, ensuring geographic balance and gender parity, and fostering two-way interaction.

Stay tuned: Unpacking the OEWG’s impact with reports and events

Grab your popcorn — it’s going to be an exciting ride! We’ll be closely following all the developments, putting together a detailed report, and organising events where we can discuss and analyse the results together. Whether you’re a seasoned observer or just curious about the process, there’s plenty to look forward to.

Prepare for the final session: Check out Breaking down the OEWG’s legacy: Hits, misses, and unfinished business — your essential briefing on the OEWG’s key achievements, shortcomings, and what to expect in this closing chapter.

Follow the final session live: Our dedicated event page will feature AI-generated session reports, updated in near real-time to help you stay on top of the discussions as they unfold.

Stay tuned for more updates and join us in unpacking what comes next!

Interested in learning more about the OEWG?

Visit our dedicated OEWG page.