How can data justice be realised practically?

2 Dec 2022 10:45h - 11:45h

Event report

Data justice is also about reclaiming the knowledge commons of social data to further individual and collective sovereignty (and all the cornerstones of the World Summit on the Information Society and the UN IGF mandate – economic and political self-determination, the ability to pursue autonomous ways to development). In the African context, data justice can be understood from the perspective of past injustices (deep structural inequalities) that still reflect how technologies operate.

Open data is the idea that access to data is a great way of breaking down the exclusive power of big data holders. It can bring greater accountability, collaborative work, and economic opportunities. However, just providing more access to data alone does not create equitable outcomes. People have different capabilities and resources to exploit that data, which benefits those that are ahead of the game. All this data is about people and communities, which implicates issues around representation, over-surveillance and under-representation (e.g., data extractivism, data colonialism). The power over data needs to rest with those that generate it. There is a need for collective and participatory data governance to try to push for greater recognition of the collective/societal impacts of data.

The international community does not have a normative consensus on data governance. Data justice is not possible under the current mechanisms that tend to perpetuate dominant positions of power. Multilateral norms, processes, and normative consensus are very important in this aspect. Any regulatory framework must clearly embed the benefits with three concepts in mind: egalitarianism, contextualising decision-making in the form of federalism, and economic rights and distributed justice.

The internet allowed the evolution of AI systems due to the increasing availability of online datasets. The problem is that they are usually gathered without consent and tend to reflect the status quo and stereotypes rather than represent reality, contaminating AI models. However, it is also possible to have equitable datasets (e.g., the Māori community is building language and speech technologies that allow them to remain in control of data). To achieve this, the objectives must be set by the people and for the people and underlined by the aim to enhance social welfare.

There is a need for regulatory frameworks and principles that enable federalism and promote initiatives like the ones in the Māori community. The challenge is to make this practical in the decision-making process. Some practical solutions may include deliberative participatory exercises and other participatory mechanisms, depending on the type of decision being made and who will be affected. Governments have the responsibility to provide data infrastructures while respecting that communities hold stewardship over the data they produce. This structure might require different types of governance. In addition, a future global system of data governance must strike a balance between public and private value creation in the digital economy (the idea of the social contract for data that sets out a bundle of rights) and establish ex-ante requirements of transparency.

By Isabella Bassani

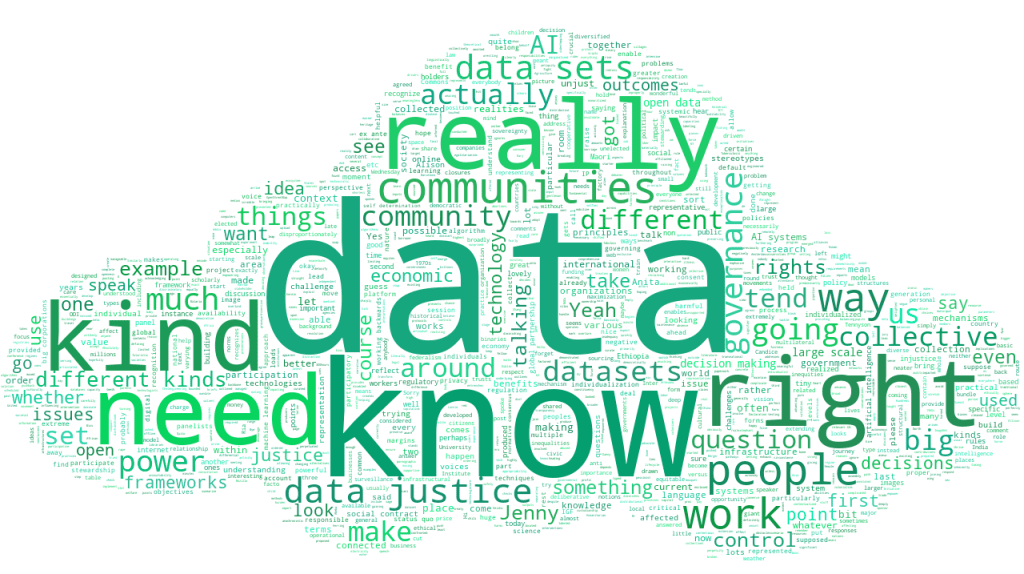

The session in keywords

Related event